BruegelNow

bruegelnow

The curious case of a Brueghel the Younger lot estimate

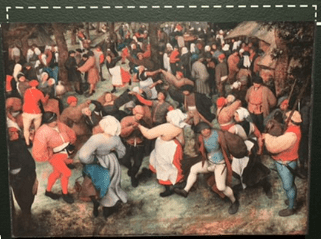

A very nice version of “Wedding Dance in the Open Air” by Pieter Brueghel the Younger is coming up for auction shortly at Christies Paris on November 21, 2024 in the auction “Maîtres Anciens : Peintures – Dessins – Sculptures” (Live auction 23018). (This work is called “The Wedding Dance” in this auction.)

The consensus is that this painting is most likely a copy of a lost work by Brueghel’s father, Pieter Bruegel the Elder. (It is also possible that the composition could be a combination of elements from various wedding dance scenes that his father painted.)

We can’t help but wonder why the estimate is so far removed from the price realized when the lot was last sold 13 years ago. When sold by Sotheby’s New York on June 9, 2011, the price realized was $512,500 on an estimate of $300,000 – $500,000.

The current estimate for the Christie’s sale is €120,000 – €180,000. Why the lot now carries an estimate 25% – 35% of the price realized in 2011 is puzzling.

While we are not an expert at setting auction estimates, such a low estimate is perplexing. In our experience, wide swings in valuation would typically occur under a few circumstances:

- Change in authorship: While the work was sold in 2011 as “Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Studio,” perhaps it was purchased with the belief that the attribution could be changed to a fully autograph work of Brueghel the Younger. However, since the price realized was not far from the estimate, this appears unlikely.

- Market for the artist’s work: Some artist’s works fluctuate in price due to the artist becoming more (or less) popular. Based on other recent Pieter Brueghel the Younger works at auction over the last few years, interest in the artist continues to be strong, and high prices achieved. It is unlikely that change of interest in Brueghel the Younger’s work resulted in a lower estimate.

- Lack of due diligence / research: As mentioned above, traditionally this work is called “Wedding Dance in the Open Air.” The current work is listed as “La Danse de Noces” (“The Wedding Dance”). Perhaps this is a careless error by Christie’s, who may not have done their research in order to properly name the work. Similarly, Christie’s may not have conducted due diligence to determine how much the work sold for when it was last at auction.

We will be closely watching the outcome of the sale to understand if the €120,000 – €180,000 is an accurate estimate, or if the hammer price will soar to the heights achieved when it was last auctioned.

Book Review: Bruegel & l’Italia / Bruegel and Italy: Proceedings of the International Conference Held in the Academica Belgica in Rome, 26-28 September 2019 (Peeters, 2023)

A fascinating new monograph assesses Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s encounter with Italian art and culture. Bruegel, like many Netherlandish artists of his era, traveled to Italy early in his career. His Italy travels are mentioned in most biographies, usually in a cursory fashion. This monograph, comprised of 11 chapters written by leading scholars in the field, takes an in-depth look into this important aspect of Bruegel’s career. It is a compelling addition to Bruegel scholarship, going beyond the superficial recounting of his travels through the region. The monograph is comprised of three sections. Part 1 reviews Italian art in the Low Countries before and during Bruegel’s time. Part II details Bruegel’s journey and his time in Italy. Part III reviews Bruegel’s dialog with Italy in his later life and work.

Bruegel’s trip to Italy has not been closely studied up to this point because no compositions after modern Italian artworks by his hand are known, and the impact of his travels is not immediately evident in his work. The monograph takes issue with this line of thought. The book makes the case that Bruegel didn’t need to travel to Italy to see Italian masters like Raphael and Michelangelo, since prints of these works were already circulating in the Low Countries and were referred by local masters. Instead, many interesting theories of Bruegel’s reasons for travel are put forward. Most interesting is that Bruegel was already employed by print maker Hieronymus Cock and his printing company, Aux Quatre Vents (Sign of the Four Winds), and embarked on the trip in order to make preparatory drawings for engravings which would be executed upon his return to Antwerp. Other authors make the case that Bruegel also undertook the journey to market his talent abroad in preparation for later print sales and painting commissions. Bruegel’s promotion of his work seems to have been particularly effective with the Farnese family, primarily Cardinal Alessandro Farnese and his circle, including his nephew and namesake.

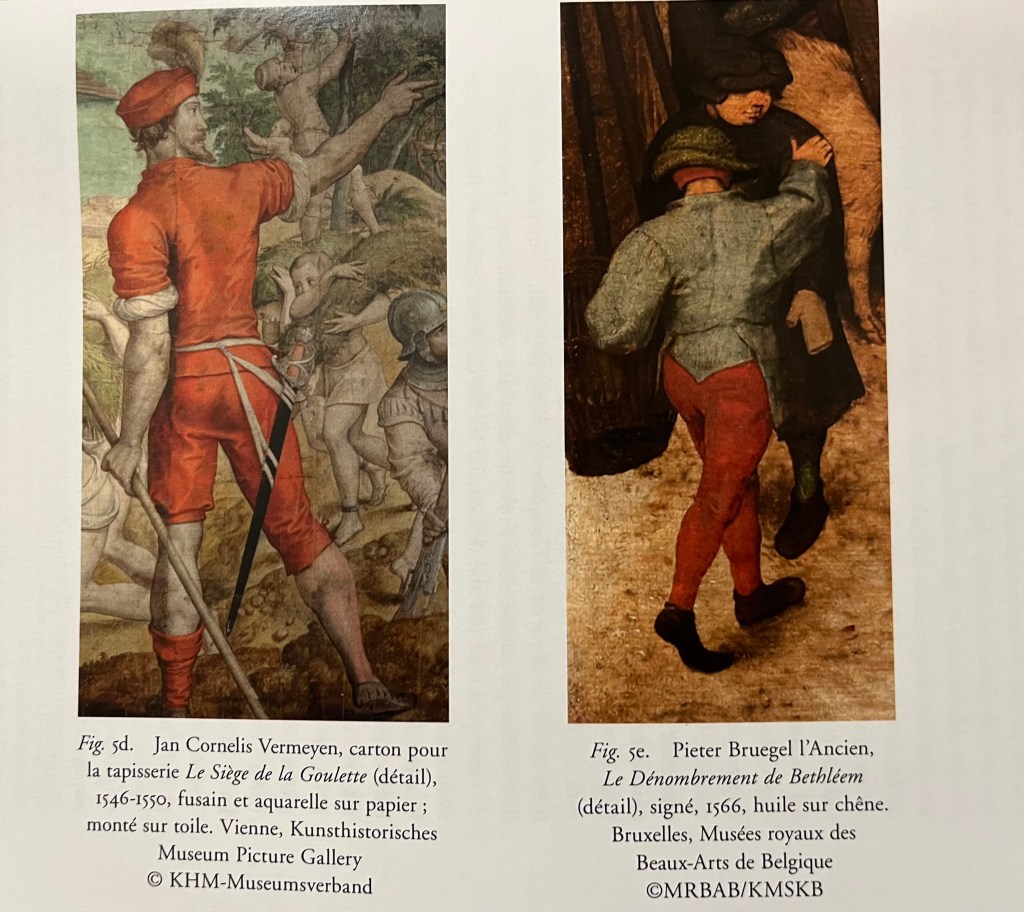

The book makes the case that Bruegel did not go to Italy to simply become familiar with ancient and modern Italian art, but instead to incorporate Italian aspects into his works. The monograph looks to reformulate Bruegel’s relation with the country as a reciprocal exchange, meaning, for example, that Bruegel was influenced by Italian art, and then Bruegel’s drawings and paintings went on to influence later Italian artists. The authors make the case that a profound impact of his time in Italy was manifested in his late panel paintings, with their large figures and energetic movements. Brueghel was likely influenced by the Italian tapestries that he viewed, with their lively, vibrant figures impacting Bruegel’s sequencing of figures in motion. An example of this possible influence is below.

The volume posits that Bruegel not only visited Rome, but he also visited Naples as well as Reggio Calabria. It is thought that he had extensive contact with artists in the region, such as the Croatian miniaturist Giulio Clovio in Lyon, France, when Bruegel was on his way to Italy.

Italy’s influence on Bruegel’s went beyond pictorial composition, and is likely to have continued with the type of material on which he painted. Two of Bruegel’s paintings, Misanthrope (1568) and Parable of the Blind (1568) now in the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, are on glue-tempera canvases, also called Tuchlein. These could have been purposely painted in this format for export to Italy since these paintings could be rolled for long distance transport.

Artistic impact is thought to have occurred with Bruegel’s The Tower of Babel, now in Vienna, where its inspiration could have occurred from Bruegel’s viewing ancient Italian buildings like the Colosseum and allusions to Romanesque architecture. However, Bruegel translates the biblical story into his time, by transporting Babel to an Antwerp-like Netherlandish city of Bruegel’s era.

While I was unable to read the chapters written in Italian, those written in English are of uniformly high quality. The chapter on Bruegel’s Bay of Naples painting, written by Tanja Michalsky, is of interest, since that work has frequently been the subject of authorship debate over the past few decades. The chapter detailing Bruegel’s Seasons paintings by Tine Luk Meganck, posits that the series of paintings was created specifically to hang on the four walls of the villa of Nicholes Jonghelink. This early example of a room installation was done to promote meal-time discussion, since it was installed in the villa’s dining room. Italian villas of the same era had a similar layout and decorations.

The monograph is highly recommended. It provides a deep dive into a previously little-known aspect of Bruegel the Elder’s life and brings forward a wealth of new information that will impact Bruegel scholarship for years to come.

Brueghel: The Family Reunion

An art museum in ‘s Hertogenbosch, Netherlands, the Het Noordbrabants Museum, is throwing a “family reunion” for the Bruegels / Brueghels. The exhibition, Brueghel: The Family Reunion, covers nearly 200 years of painting from this famous family. The exhibition covers five generations of the Bruegel family, including his sons, grandchildren and mother-in-law. All were influential painters, creating a dynasty throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth century. The family was responsible for the “Bruegel craze” that occurred around 1600, after the most famous member of the family, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, had died. The exhibit is captured in a compelling monograph with wonderful essays published by WBOOKS (www.wbooks.com).

The head of the dynasty, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, is represented in the exhibition by several paintings which seldom leave their home museum. Or, in the case of “The Drunkard Pushed into the Pigsty,” from 1557, are on a rare loan from a private collection.

The role of the women in the Bruegel family is a focus of the monograph. After Pieter Bruegel the Elder died, Pieter the Younger and Jan the Elder, who were very young children, were taught to paint by Bruegel’s mother in law, Mayken Verhulst. Mayken was an artist in her own right, who took over the daily business operations of the workshop of her husband, Pieter Coecke Van Aelst’s, after he died. She not only transferred her artistic knowledge, with documentary evidence showing that she instructed Jan Brueghel the Elder in watercolor painting, but also business knowledge related to how to run a large-scale workshop, which both Pieter the younger and Jan the Elder, did later in life.

The Brueghel family’s interest in the outside world, including elemental and seasonal cycles , depicting plants, animals and weather patterns, can be found in select paintings of the family members. Jan Brueghel the Elder specialized early on in landscapes and the elements. The monograph depicts a series of one of the earliest series, which was so popular it was copied with variations into the 17th century, by not only Jan, but by his son Jan Brueghel the Younger. David Teniers the Younger, the son-in-law of Jan Brueghel the Elder, turned his attention to weather phenomena, and used masterful brushstrokes to evoke emotion.

Paintings of collectors’ cabinets began with Jan Brueghel the Elder and continued for generations, including a fine example by Jan van Kessel included in the monograph. Nearly one-quarter of his surviving oeuvre are depictions of insects. Many works have van Kessel painting the letters of his name in the form of caterpillars and snakes, tying art and nature together. Painters such as Jan Brueghel and Jan van Kessel studied nature and objects with an eye for detail, creating depictions so accurate that they could “seduce and deceive the eye of the viewer.”

The final chapter of the monograph focuses on women and artistic knowledge in the family, with a focus on Clara Eugenia, eighth child of Jan Brueghel I and Catharina van Marienbergh. Clara Eugenia chose to live her life in a semi-monastic residential community for women. Called Beguines, these communities offered women a supportive alternative to marriage and motherhood. Clara Eugenia took the post of church mistress and served as godmother not only for her brother Jan II’s daughter, but also for Clara Teniers, daughter of her sister Anna and David Teniers II. A wonderful portrait of Clara Eugenia is presented in the exhibit and monograph.

The bright, bright vibrant reproductions of the paintings in the monograph make this an essential work for those interested in the Bruegel family. While viewing the works in person should be a priority for those in the region, for others who are not able to attend (or for those that want a wonderful memento), this monograph is a wonderful substitute.

Klaus Ertz, 1945 – 2023

Klaus Ertz, who created catalog raisonnés of members of the Brueghel family and other painters of that era, has died. His death was announced on website of his self publishing company, http://www.luca-verlag.de/publisher. Ertz, and his wife, Christa Nitze-ErtzCristina, spent decades creating catalog raisonnes of members of the Brueghel family, including Jan Brueghel the Elder (1979), Jan Brueghel the Younger (1984) and Pieter Brueghel the Younger (2000, 2 volumes).

The books were carefully created, virtual works of arts themselves. I have always been particulalry impressed by the 2 volumes related to Pieter Brueghel the Younder. The approximately 1,400 works presented over hundreds of pages overflowed with many color images of Bruehgel’s works. For example, Ertz cataloged (with many images) some 127 versions of “Winter Landscape with Ice Skaters and Bird Trap.”

The monographs saught to differentiate autograph works created by Bruehgel the Younger from works primarily by the hands of the many assistents employed in his workshop. Ertz also noted works that were signed and dated.

His greatest impact on the art market was his authentication of works from the Bruehgel family for auction houses like Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Koller and others. The auction houses to bring some level of order to the, if not quite chaos, certainly unclear authorship, of Brueghel’s works. According to a fascinating study (“The Implicit Value of Arts Experts: The Case of Klaus Ertz and Pieter Brueghel the Younger,” Anne-Sophie Radermecker, Victor A. Ginsburgh and Denni Tommasi, January 2017, SSRN Electronic Journal), an Ertz authentication of a work by Pieter Brueghel the Younger increased the work’s value by 60%. While the authentication documents that Ertz created for auction houses were typically short in length, their impact added hundred of thousands of dollars to the sale price of Brueghel-related works. Ertz and the auction houses seemed to have a symbiotic, and very mutually beneficial, relationship.

How Ertz’s death will impact the auction houses, as they will inevitably continue to sell works by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, is an open question. In the brief time since Ertz’s death, only one auction with a Pieter Brueghel the Younger work has been announced (as far as we can ascertain). The work, “The Adoration of the Magi,” was authenticated by Ertz in 2009. Because Ertz authenticated such a large number of paintings during his lifetime, if the owners / auction houses can produce Ertz’s previously created authentication letters, many works will be continue to be sold as verified by Ertz.

Since Ertz began producing his volumes some 40 years ago, many changes have occurred with connoisseurship, catalog raisonnés and their definition and creation. Unsurprisingly, cataloging artist’s works have moved online. For example, a wonderful Jan Brueghel the Elder compendium has been created and overseen by Elizabeth Alice Honig, Professor, University of Maryland, and her team at http://janbrueghel.net/.

As recounted in the Radermecker, Ginsburgh and Tommasi article, expertise in the form of purely visual connoisseurship that Ertz provided has been supplanted by evidence-based technical analysis of the kind applied to the Bruegel family in the groundbreaking volume “The Brueg(H)el Phenomenon: Paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Pieter Brueghel the Younger” by Christina Currie and Dominique Allart. This is because technical analysis provides stronger grounds for securing authorship than a simple visual review of a painting. However, detailed technical analysis is much more time consuming and expensive, making the proposition of technical analysis becoming commonplace at auction houses unlikely in the short term. How art market authentication of the Brueghel family’s works moves forward in the wake Ertz’s death has yet to be seen.

Book Review: “Peasants and Proverbs: Pieter Brueghel the Younger as Moralist and Entrepreneur”

“Peasants and Proverbs: Pieter Brueghel the Younger as Moralist and Entrepreneur” – Edited by Robert Wenley, with Essays by Jamie L. Edwards, Ruth Bubb, and Christina Currie. Published to accompany the exhibition at The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham in association with Paul Holberton Publishing.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

This volume makes an excellent case regarding why Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s works became popular throughout Europe in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. While Bruegel the Elder’s painted works were primarily in the private collections of the Pope and noble families, his eldest son, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, was producing copies of his father’s compositions for decades. These works were largely bought by middle and upper-class European families, cementing Bruegel/Brueghel’s legacy and furthering the family’s “brand.”

It is rare for a museum exhibition to conduct a deep-dive into a single Brueghel the Younger work, which makes this show (and monograph) especially welcome. The focus is on four works of the same subject, “Two Peasants binding Firewood.” Thought to possibly be a model of a lost painting by Bruegel the Elder, Pieter the Younger painted multiple copies of this work, with four included in this exhibit (three of which are thought to come from Brueghel the Younger and his workshop).

Mysteries surround “Two Peasants binding Firewood.” Why did this subject matter resonate with Europeans at the time? How many versions of the painting were created? How were the copies made? The essays in the monograph seek to answer these questions in fascinating detail.

The book begins with a chapter detailing the life of Pieter Brueghel the Younger. Born in 1564, his famous father, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, died when Pieter the Younger was a young child. Pieter the Younger moved to Antwerp and set up his own independent studio, specializing in reproductions of famous works by his father, as well as original compositions in the Elder Bruegel’s style. Brueghel the Younger was assisted by a rotating group of one or two formal apprentices that entered his workshop every few years. Brueghel the Younger and his assistants produced paintings at high volume throughout his career, with Pieter living a long life, dying in 1637/1638.

The next chapter is Jamie L. Edward’s engaging essay detailing the history of peasants in Bruegel the Elder and Brueghel the Younger’s works. Interestingly, the meaning of the painting at the center of the exhibit, “Two Peasants binding Firewood,” cannot be ascertained with certainty, but can be surmised based on the appearance of similar peasants in other Bruegel works. Of the two peasants prominent in the painting, the tall thin peasant, wearing a bandage around his head, has been identified as a reference to the proverb ‘he has a toothache at someone,’ meaning someone that deceives or is a malingerer. The second peasant, stout and dressed in red pants, represents a stock ‘type’ which can frequently be found in peasant wedding paintings of the time. One likely reading of the painting is that it depicts two peasants who have been caught in the act of stealing firewood.

The chapter by Christina Currie and Ruth Bubb focuses on an analysis of the two other extant rectangular versions of “Two Peasants binding Firewood,” (one from a Belgium private collection and the other at the National Gallery, Prague), comparing them to the version at the Barber Institute. A surprising finding of the dendrochronological analysis of the painting at the Barber Institute found that the tree used to fashion the board used in the painting was cut down between ~1449 and 1481. The authors identify the creator of the panel through a maker’s mark on the reverse of the painting. The panel maker was active from 1589 – c.1621, meaning that the panel was likely painted during this time frame. Interestingly, this means that the tree was stored for well over 100 years before being used by the panel-maker to create the board used by Brueghel the Younger.

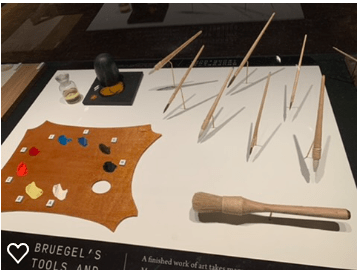

Brueghel typically made his works by transferring images via a cartoon to the prepared panel through pouncing, which involved rubbing a small porous bag containing black pigment over holes pricked in an outline of the painting (called a cartoon) onto the prepared blank surface of the panel. The dots that remained were connected via black graphite pencil, and the pigment (dots) wiped away. The paint layer was then placed on top of the underdrawing.

The authors review each of the three rectangular versions, identifying two as autograph versions by Pieter the Younger and his studio. The authors make a compelling case for the version of the painting now in Prague being created outside of Pieter the Younger’s studio. This is due to several reasons, including the lack of underdrawing. The Prague version is also more thickly painted and has relatively crude color-blending in the faces. Some colors in the painting are also different, with light blue rather than pink used for the color of the jacket of the plump peasant.

The final section of the monograph contains the catalog of works in the exhibition. The detailed description and wonderfully-produced images allow the reader to analyze them individually as well as to compare and contrast them. For example, one version of the painting seems to show the thin peasant with his mouth open, showing his few remaining teeth.

Particularly interesting is the smaller, round version of the painting, said to have been painted by Brueghel the Younger later in his career, using free hand, and not a cartoon. This version depicts the two peasants with much smaller heads, in a loose, free-hand manner.

The description of the paintings and their differences is fascinating, with the reader coming away with a good understanding of how the paintings were created and who likely painted them. Readers of the monograph will learn the fascinating history of the Bruegel/Brueghel family along with a compelling explanation regarding how Brueghel the Younger continued and enhanced his family’s reputation in the first part of the 17th century.

Book Review: Anonymous Art at Auction

The Reception of Early Flemish Paintings in the Western Art Market (1946–2015) by Anne-Sophie V. Radermecker

“What’s in a name?” Not in the Romeo and Juliet sense, but in terms of old master paintings, we know that an artist’s name is inextricably tied to a work’s market value. A work authenticated as painted by “Pieter Brueghel the Younger” commands a massive premium compared to a work whose authorship is listed as “after Pieter Brueghel the Younger” or “school of Pieter Brueghel the Younger.”

But when a work of art cannot be definitively tied to an artist, are there factors of an anonymous painting that impacts the price the work can command in the marketplace? This question is explored in a fascinating new volume, “Anonymous Art at Auction: The Reception of Early Flemish Paintings in the Western Art Market (1946 – 2015),” by Anne-Sophie V. Radermecker (Brill, 2021). This is a must-read for those who want to better understand the features that impact the market value of anonymous Flemish art.

Radermecker was a co-author of a 2017 article, “The Value Added by Arts Experts: The Case of Klaus Ertz and Pieter Brueghel the Younger,” which researched the impact of an art expert’s opinion on the market price for Brueghel the Younger’s paintings at auction. The authors concluded that when Klaus Ertz, the author of Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s catalog raisonne, provided authentication for a Brueghel work, it had a meaningful impact on the price paid. Buyers paid roughly 60 percent more for works authenticated by Klaus Ertz than works without authentication.

Radermecker’s current monograph makes clear from the outset that an artist’s name is the equivalent of a “brand.” But what about the thousands of paintings for which the artist in unknown? The book details the market reception of indirect names, provisional names, and spatiotemporal designations, which are identification strategies that experts and art historians have developed to overcome anonymity.

Building a brand name during an artist’s lifetime was clearly important, conveying three key attributes: recognition, reputation, and popularity. But because many paintings were not signed, the scholarly community used stand-in authorship titles for works that were painted by the same artist or studio.

These stand-ins for names act as identifiers and play a role in determining a work’s economic value. Example of stand-ins for names include “Master of the female Half-Lengths,” “Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy,” and “Master of the Prado Redemption.” This volume points out that value increases when works are ascribed to a painter, in the form of a stand-in name, when the true author’s name is not known.

By ascribing identities for works without named authors, authorship uncertainty is reduced, and new, alternative brands are created. The reduction of authorship uncertainty leads a buyer to feel more confidence in a work, which adds to buyer’s willingness to pay higher prices. Interestingly, the author suggests that the somewhat haphazard nature of application of name labels over the period of the study (1946 – 2015) was a stumbling block that diminished the efficacy of labels.

The author defines a broad set of stakeholders, including art historians, experts, curators, restorers, dealers, etc., who are involved in proposing and establishing names for otherwise anonymous artists. The author makes the point that while the motives of parties from the scholarly field are not theoretically commercial in nature, they must understand their considerable impact on the market.

Further, Radermecker makes the case for the impact of the scholarly field when ascribing certain works as “significant” or disparaging works by referring to their authors as “minor masters” or “pale copyists.” The role of museums as authorities is discussed in the context of historicizing and legitimizing artistic output. The author argues that museums can place artist brands as well as anonymous artist in context and help the general public understand the value conveyed by artist brands.

The book details the curious fact that an objectively lower-quality work linked to a known artist (and their brand) can command significantly higher price than a higher-quality work that is not connected with secure authorship or artist brand.

Further complicating authorship is the very real studio environment in which Netherlandish artists worked. The old master as a “lonely genius” which solely created paintings is a very nineteenth-century notion and colors the market still today. Research conducted over the past 50 years has shown that most artists did not work alone but were frequently part of a larger workshop. The attribution of many paintings continues to be given to a sole artist when the actual participation of the artist and their workshop often varied greatly.

A case is made for anonymous works providing an alternative artistic experience than those of brand name artists. Without artist’s names, the viewer (and potential buyer) focuses on the physical object and its properties in order to provide an option on the work, which then leads to a value determination.

In an intriguing chapter titled “Paintings without Names,” the market reception of painting that lack all nominal designations was analyzed. A sample of 1,578 auction sales results were put through regression analysis, with the finding that works labeled “Netherlandish” were, on average, 22.6% more expensive than works labeled “Flemish.” Further, works that contain the names of locations where major masters settled and created their work also led to higher valuations. Specifically, works labeled “Antwerp” and “Bruges” commanded +30.6% and +59.2% higher prices. The author concludes that these city names not only function as a location of origin, but also as a label of quality related to the artistic hub.

The author has created a nomenclature made up of eight designations that each had a different impact upon sale price, depending on the specificity of the information provided. Designations specifying a work’s location of production led to prices that are higher on average, as noted above. The author also found that 3 other factors were correlated with higher prices – the work’s state of preservation, the length of catalog notes (which in theory correlate to an expert’s potential involvement) and the mention of earlier attributions.

Radermecker‘s thorough analysis and thought-provoking conclusions provide stakeholders (particularly auction houses) with valuable information to leverage when working to maximize the price paid for anonymous artworks.

The Bruegel Success Story: Papers Presented at Symposium XXI for the Study of Underdrawing and Technology in Painting, Brussels, 12 – 14 September 2018 (Edited by Christina Currie, in collaboration with Dominique Allart, Bart Fransen, Cyriel Stroo and Dominique Vanwijnsberghe (Peeters, 2021))- Monograph Review

The 450 anniversary of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s death, in 2019, ushered in many exciting projects to commemorate the milestone. Perhaps none as rich and diverse as this conference and accompanying 550-page monograph, which included groundbreaking papers on all aspects of the Bruegel family.

I was fortunate to attend the conference and can happily replace my scribbled notes and crude drawings created when seated in the audience with this exquisite monograph. It is perhaps the most beautifully illustrated Bruegel monograph based on conference papers that I’ve ever seen. Many of the Bruegel paintings reproduced in the monograph were recently cleaned and restored, which the monograph fully captures with large, rich illustrations. Not only are the paintings themselves reproduced, but enlarged details of critical sections of the paintings are featured.

The monograph’s first section includes a series of articles on the newly restored Dulle Griet, done in preparation for the Bruegel exhibition at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna in 2018 -19, in conjunction with the Museum Mayer Vanden Bergh in Antwerp, where the painting hangs. The conference brought to light that Dulle Griet was likely transferred from cartoon tracings after Bruegel carefully worked out the picture on other media. The recent cleaning of the panel has uncovered that many of the painting’s pigments have faded or darkened. The cleaning exposed a vital missing feature of the painting, the date of execution of the work. A fascinating essay details a colored drawing of Dulle Griet, housed at the Kunstpalast, Dusseldorf. The drawing helps convey the painting’s original colors which have faded over the years. The analysis of the paper on which the drawing was rendered revealed a watermark from no earlier than 1578, confirming its status as a copy.

The second section of the monograph is devoted to a group of papers related to Pieter Bruegel the Elder and his practices. Groundbreaking scholarship considers Bruegel’s paintings on distemper on lined canvas (Tuchlein), a format which Bruegel was one of the last to utilize. Essays on The Adoration of the Magi (in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Belgium), by Veronique Bucken, provide intriguing details about this format of painting.

Bruegel used a variety of methods to paint his monumental panel paintings. For example, compared to Dulle Griet, the Detroit Wedding Dance, was drawn free hand using an “extensive and vigorous drawing with numerous adjustments to the modeling and shading of the figures, but not the composition as a whole.” Another surprise is the finding that the Wedding Dance was altered from its initial composition size through the addition of a top border. This is discussed in an intriguing paper by Marie Postec and Pascale Fraiture that compares the Detroit version with a little studied copy after Bruegel the Elder in Antwerp.

The third section of the monograph is devoted to Jan Brueghel, son of Pieter the Elder. Several essays review the difference between Jan and his elder brother, Pieter the Younger, in terms of creating copies after their father’s works. Elizabeth Alice Honig’s “Copia, Copying and Painterly Eloquence,” describes Jan Brueghel the Elder and the notion of copia, as articulated for a Renaissance audience by Erasmus in his De Copia. In Uta Neidhardt’s paper, “The Master of the Dresden Landscape with the Continence of Scipio: A Journeyman in the studio of Jan Brueghel the Elder?” identifies two different “hands” working in Jan Brueghel’s studio. The essay is important because so little is known about those painters that worked in proximity to Jan’s studio. The essay remarks on the difficulty in assigning works to specific studio hands. (An issue that was on display just last month, when Christie’s sold a work dated 1608 stamped in copper by “Pieter Brueghel III,” owning to what is undoubtedly a spurious signature.) Larry Silver’s essay “Sibling Rivalry: Jan Brueghel’s Rediscovered Early Crucifixion,” focuses on the difference between Jan the Elder and Pieter the Younger’s treatment of a lost composition of Pieter the Elder. As can be seen frequently in the brother’s work, Jan the Elder creatively re-invents works based on his father’s design, while Pieter the Younger copies his father’s works in a fairly precise manner.

Section four investigates Bruegel’s network and legacies. The question of who painted some of the works after Bruegel the Elder’s untimely death in 1569 and his sons first paintings decades later remains a key mystery yet to be solved. Intriguing essays related to Bruegel’s networks, contracts and connection to homes and studios in Antwerp help put pieces of the puzzle together. Lost works like The Heath allow us to ponder questions of authorship and the number and varieties of copies made (most likely) by non-Brueghels.

The Bruegel “craze” of the early years of the 1600’s and the aftermath of Bruegel’s death is also covered in this section, which details the many ramifications of the aftermath of Bruegel The Elder’s untimely death. The monograph is rife with intriguing aspects of Bruegel’s legacy, including “Peasant Passions: Pieter Bruegel and his Aftermath” (Ethan Matt Kavaler) and “In Search of the Bruegel’s Family Homes and Studios in Antwerp” (Petra Maclot).

The devotion of eight pages to the restored Dulle Griet in an addendum of the monograph speaks to the exquisite care taken to showcase the paintings of Bruegel and his family.

That the quality of the monograph, with all of its finely detailed images, matches the uniformly high quality of the papers within, is a testament to the care that went into creating this handsome volume. It is wonderful that the conference papers are presented in such rich surroundings.

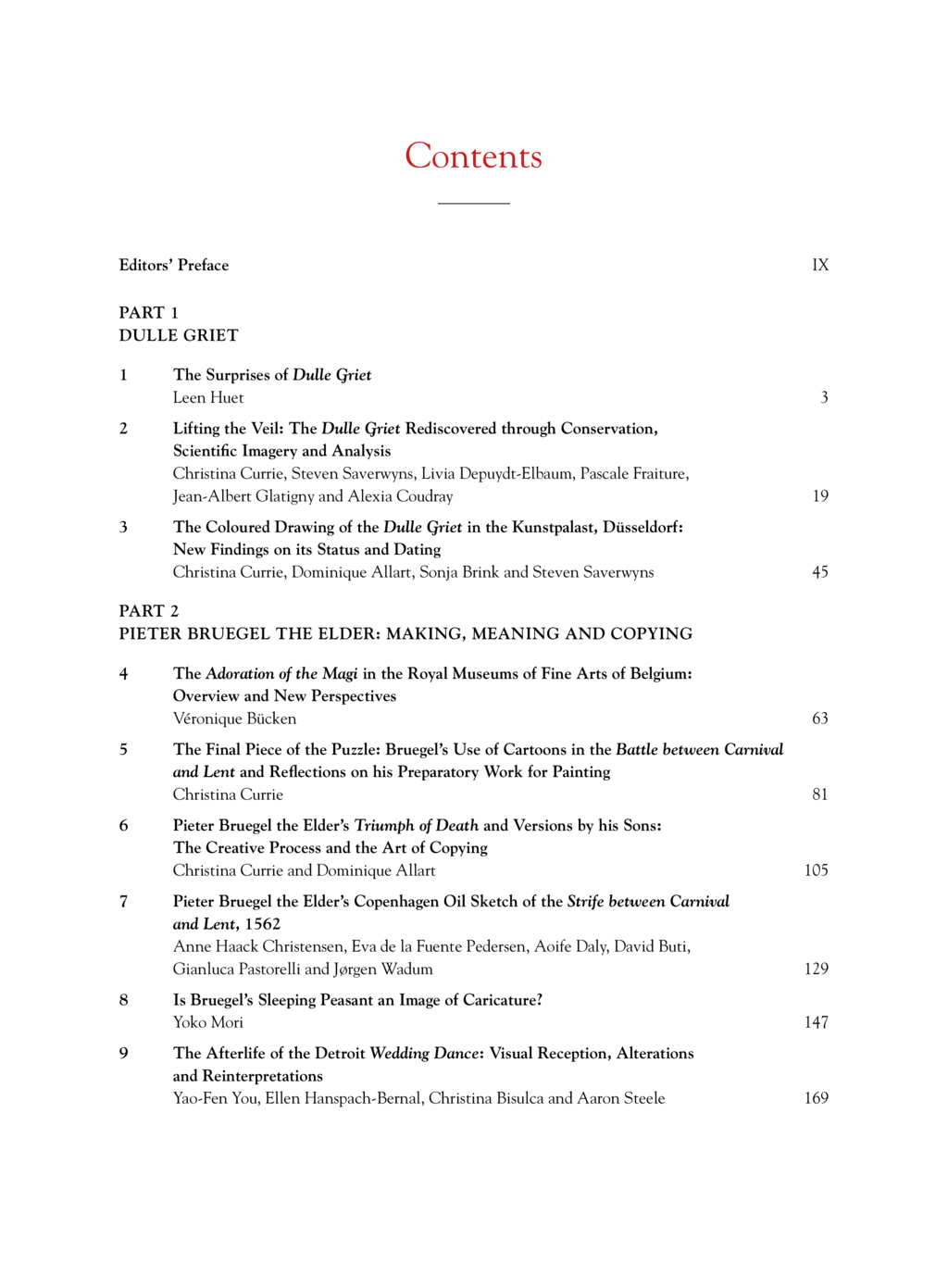

The full table of contents of this stunning monograph is below:

The Wedding Dance – Revealed

The marvelous Pieter Bruegel the Elder exhibit at the Detroit Institute of Arts Museum (DIA), interrupted by the Coronavirus, focuses on Bruegel’s celebrated The Wedding Dance, bought in 1930 by then-museum director William Valentnier. The exhibition is the result of many years of research by the DIA team, which uncovered remarkable new information about the painting including:

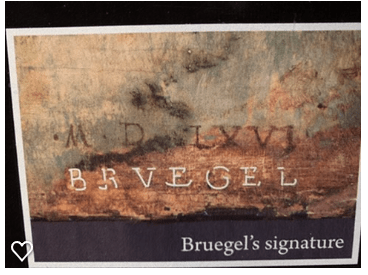

- Bruegel the Elder’s signature: Previously the DIA painting was the only dated but unsigned of Bruegel the Elder’s works. Thanks to the efforts of the DIA imaging team, led by Aaron Steele, the signature was discovered during imaging and technical examination. The signature was located below the “MDLXVI” (“1566”) execution date, which was first noticed when the painting arrived at the DIA in 1930. The signature’s discovery provides a basis for aligning the work with other autograph Bruegel the Elder paintings. Interestingly, the Wedding Dance also contains painting guidelines, which are nearly invisible lines that helps artists correctly position the characters of signatures / dates.

- Alteration of the paintings size: Following other recent discoveries of Bruegel’s paintings being altered in size, the size of this work too was altered. While other Bruegel the Elder works have been reduced in size, The Wedding Dance was instead enlarged after it had been painted. The original top of the painting ended with what can only be characterized as an abrupt stop, cutting off the top portion of several figures and landscape objects. The DIA research team discovered that an additional strip was added to the top edge of the wooden panel to provide a horizon line to the painting, making it similar to other Bruegel the Elder works.

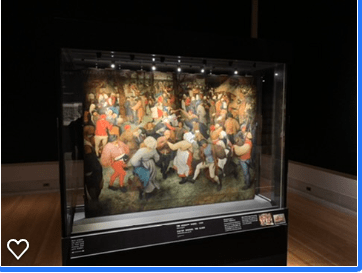

What makes this exhibit particularly striking is the presentation of the painting in an enclosed glass case, allowing it to be viewed from the back and sides (see photos). This provides the viewer an ability to closely view the thin board on which this masterpiece was painted.

A marvelous companion Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts (Volume 92, number 1, 2019) was published as a companion to the exhibit. Congratulations to the DIA team, including Ellen Hanspach-Bernal, Christina Bisulca, Yao-Fen You, Katherine Campbell, Becca Goodman, Blair Baily and Aaron Steele for a truly fantastic exhibit! (The DIA is scheduled to reopen on June 30, 2020).

A Rediscovered Bruegel?

A new book puts forward the thesis that Dancing Peasants at a St. Sebastian’s Kermis, long attributed to a follower of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, was in fact painted by the Elder Bruegel. Maximiliaan P.J. Martens, on the Faculty of Arts and Philosophy at the University of Gent, makes this startling claim in Dancing Peasants at a St. Sebastian’s Kermis: A Rediscovered Painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Silvana Editoriale, 2019).

Martens saw the painting in 2016 and recognized the hand of Pieter Bruegel the Elder under multiple layers of old retouching and over paint. Martens makes a compelling case that similar typology of figures, materials and objects in Dancing Peasants at a St. Sebastian’s Kermis are spread throughout Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s oeuvre. He also puts forward the notion that the painting’s style is very similar to the elder Bruegel’s work. Subsequent technical examination and careful cleaning revealed numerous features characteristic of the master’s style and technique, according to Martens

A scientific analysis was conducted on the materials, which, combined with the observation of how they were employed, led Martens to the conclusion that the works was by the hand of the elder Bruegel. The painting is made up of oak quarterly split boards with slanting that is typical of the type that Bruegel employed, which were butt joined with dowels. The panel was prepared with calcite mixed with animal glue and has and has an imprimatur consisting of a brownish ochre hue with lead white and particles of carbon black mixed in, again typical of the elder Bruegel.

Martens notes that the underdrawing is invisible to the naked eye, and even hard to distinguish through infrared reflectography. He concludes that as with a large number of other Bruegel paintings, it was likely traced from a 1:1 cartoon. The tracing was reinforced in a liquid material, likely to be identified as black carbonaceous ink. He notes that pigments that have been identified fits the palette from other paintings by Bruegel. Martens attributes the painting to late in the artist’s career, around 1567–1569.

Martens was not the first to attribute the painting to Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The eminent art historian Max J. Friedländer similarly attributed to Bruegel the elder in the early 20th century.

One area of research not detailed in the monograph is a dendrocronological analysis of the boards used in the paintings. Sotheby’s included an analysis when the work was sold in 2016 and noted:

The latest ring present in the lower plank is sapwood and is datable to 1566. The last rings of the upper two planks are heartwood and are datable to 1562 and 1563. Adding the standard minimum eight years of expected sapwood growth to the last registered ring of heartwood in the upper two planks suggests a usage date of 1571 or after.

Of course, if this analysis is correct, the painting would have been executed after Bruegel the Elder’s death in 1569. We look forward to learning Martens’ dendrocronological analysis, which the author indicated is forthcoming.

The work appeared last at auction in 2016 at Sotheby’s London, selling for £156,250 after an estimate of £80,000 – £120,000. If the attribution to Bruegel the Elder holds, the work will be worth millions, making this one of the greatest returns on investment of an Old Master painting in recent years.

Tags: Brueghel, Bruegel the Elder, Brueghel the Younger, dendrocronology, Max J. Friedländer, Dancing Peasants at a St. Sebastian’s Kermis: A Rediscovered Painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Silvana Editoriale

Bruegel The Master: A Crucial New Monograph

The new monograph, Bruegel The Master, published by Thames & Hudson, is a highly engaging tour through Pieter Bruegel The Elder’s print and painting oeuvre. Published in conjunction with the recently concluded exhibition in Vienna, the monograph details Bruegel’s corpus of prints and paintings. Best of all, the monograph includes recent research into Bruegel’s painting techniques undertaken in advance of the Vienna exhibition.

Many Bruegel monographs divide his output by format, with separate sections on his prints and paintings. Bruegel The Master instead weaves both print and paintings together in a roughly chronological review of his output, while delving into the fascinating process undertaken by Bruegel to create his masterpieces. The monograph details Bruegel’s painting techniques, which differed greatly between works. For example, his earlier painted works, such as Children’s Games, The Battle Between Carnival and Lent and Christ Carrying the Cross, have precise, mechanical figure contours, suggesting the transfer of image using a cartoon. In contract, Bruegel’s later works, such as his series of the months (which include The Return of the Heard and The Gloomy Day), have loose and sketchy underdrawings. For these later works, Bruegel’s painting process could only have been possible by preparing a precise conception of the painting prior to beginning his work.

One of the biggest revelations in Bruegel the Master is that many of his paintings were cut down from their original size. Such well-known works as The Suicide of Saul, The Tower of Babel, and The Conversion of Saul are specific examples of works that were altered. The reason for their being cut down remains an intriguing mystery yet to be solved.

The monograph is rife with comparisons, using infrared reflectograms, between the final painting and the preparatory under drawing. This analysis draws the reader into the book and asks them to study the images carefully. For example, a corpse visible in the under drawing of Children’s Games is covered by paint in the final paint layer, as are two children lying on the ground in front of a church, which was also overpainted.

Several works were cleaned in preparation for the exhibit. Some of the cleaning, such as for The Suicide of Saul, is dramatically presented in the book, shown mid-cleaning.

There are five additional essays available online that can be unlocked with a code found in the monograph. These essays take a deeper dive into aspects of Bruegel’s art, including Bruegel’s creative process, his painting materials and techniques, and the history of the works now in Vienna.

It would be nearly impossible for those interested in early Renaissance art history not to be thoroughly engaged by this monograph, as it engages readers in both new historical findings and timeless Bruegelian imagery.

This monograph is an indispensable addition to Bruegel art historical literature.