BruegelNow

Uncategorized

The curious case of a Brueghel the Younger lot estimate

A very nice version of “Wedding Dance in the Open Air” by Pieter Brueghel the Younger is coming up for auction shortly at Christies Paris on November 21, 2024 in the auction “Maîtres Anciens : Peintures – Dessins – Sculptures” (Live auction 23018). (This work is called “The Wedding Dance” in this auction.)

The consensus is that this painting is most likely a copy of a lost work by Brueghel’s father, Pieter Bruegel the Elder. (It is also possible that the composition could be a combination of elements from various wedding dance scenes that his father painted.)

We can’t help but wonder why the estimate is so far removed from the price realized when the lot was last sold 13 years ago. When sold by Sotheby’s New York on June 9, 2011, the price realized was $512,500 on an estimate of $300,000 – $500,000.

The current estimate for the Christie’s sale is €120,000 – €180,000. Why the lot now carries an estimate 25% – 35% of the price realized in 2011 is puzzling.

While we are not an expert at setting auction estimates, such a low estimate is perplexing. In our experience, wide swings in valuation would typically occur under a few circumstances:

- Change in authorship: While the work was sold in 2011 as “Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Studio,” perhaps it was purchased with the belief that the attribution could be changed to a fully autograph work of Brueghel the Younger. However, since the price realized was not far from the estimate, this appears unlikely.

- Market for the artist’s work: Some artist’s works fluctuate in price due to the artist becoming more (or less) popular. Based on other recent Pieter Brueghel the Younger works at auction over the last few years, interest in the artist continues to be strong, and high prices achieved. It is unlikely that change of interest in Brueghel the Younger’s work resulted in a lower estimate.

- Lack of due diligence / research: As mentioned above, traditionally this work is called “Wedding Dance in the Open Air.” The current work is listed as “La Danse de Noces” (“The Wedding Dance”). Perhaps this is a careless error by Christie’s, who may not have done their research in order to properly name the work. Similarly, Christie’s may not have conducted due diligence to determine how much the work sold for when it was last at auction.

We will be closely watching the outcome of the sale to understand if the €120,000 – €180,000 is an accurate estimate, or if the hammer price will soar to the heights achieved when it was last auctioned.

Brueghel: The Family Reunion

An art museum in ‘s Hertogenbosch, Netherlands, the Het Noordbrabants Museum, is throwing a “family reunion” for the Bruegels / Brueghels. The exhibition, Brueghel: The Family Reunion, covers nearly 200 years of painting from this famous family. The exhibition covers five generations of the Bruegel family, including his sons, grandchildren and mother-in-law. All were influential painters, creating a dynasty throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth century. The family was responsible for the “Bruegel craze” that occurred around 1600, after the most famous member of the family, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, had died. The exhibit is captured in a compelling monograph with wonderful essays published by WBOOKS (www.wbooks.com).

The head of the dynasty, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, is represented in the exhibition by several paintings which seldom leave their home museum. Or, in the case of “The Drunkard Pushed into the Pigsty,” from 1557, are on a rare loan from a private collection.

The role of the women in the Bruegel family is a focus of the monograph. After Pieter Bruegel the Elder died, Pieter the Younger and Jan the Elder, who were very young children, were taught to paint by Bruegel’s mother in law, Mayken Verhulst. Mayken was an artist in her own right, who took over the daily business operations of the workshop of her husband, Pieter Coecke Van Aelst’s, after he died. She not only transferred her artistic knowledge, with documentary evidence showing that she instructed Jan Brueghel the Elder in watercolor painting, but also business knowledge related to how to run a large-scale workshop, which both Pieter the younger and Jan the Elder, did later in life.

The Brueghel family’s interest in the outside world, including elemental and seasonal cycles , depicting plants, animals and weather patterns, can be found in select paintings of the family members. Jan Brueghel the Elder specialized early on in landscapes and the elements. The monograph depicts a series of one of the earliest series, which was so popular it was copied with variations into the 17th century, by not only Jan, but by his son Jan Brueghel the Younger. David Teniers the Younger, the son-in-law of Jan Brueghel the Elder, turned his attention to weather phenomena, and used masterful brushstrokes to evoke emotion.

Paintings of collectors’ cabinets began with Jan Brueghel the Elder and continued for generations, including a fine example by Jan van Kessel included in the monograph. Nearly one-quarter of his surviving oeuvre are depictions of insects. Many works have van Kessel painting the letters of his name in the form of caterpillars and snakes, tying art and nature together. Painters such as Jan Brueghel and Jan van Kessel studied nature and objects with an eye for detail, creating depictions so accurate that they could “seduce and deceive the eye of the viewer.”

The final chapter of the monograph focuses on women and artistic knowledge in the family, with a focus on Clara Eugenia, eighth child of Jan Brueghel I and Catharina van Marienbergh. Clara Eugenia chose to live her life in a semi-monastic residential community for women. Called Beguines, these communities offered women a supportive alternative to marriage and motherhood. Clara Eugenia took the post of church mistress and served as godmother not only for her brother Jan II’s daughter, but also for Clara Teniers, daughter of her sister Anna and David Teniers II. A wonderful portrait of Clara Eugenia is presented in the exhibit and monograph.

The bright, bright vibrant reproductions of the paintings in the monograph make this an essential work for those interested in the Bruegel family. While viewing the works in person should be a priority for those in the region, for others who are not able to attend (or for those that want a wonderful memento), this monograph is a wonderful substitute.

Klaus Ertz, 1945 – 2023

Klaus Ertz, who created catalog raisonnés of members of the Brueghel family and other painters of that era, has died. His death was announced on website of his self publishing company, http://www.luca-verlag.de/publisher. Ertz, and his wife, Christa Nitze-ErtzCristina, spent decades creating catalog raisonnes of members of the Brueghel family, including Jan Brueghel the Elder (1979), Jan Brueghel the Younger (1984) and Pieter Brueghel the Younger (2000, 2 volumes).

The books were carefully created, virtual works of arts themselves. I have always been particulalry impressed by the 2 volumes related to Pieter Brueghel the Younder. The approximately 1,400 works presented over hundreds of pages overflowed with many color images of Bruehgel’s works. For example, Ertz cataloged (with many images) some 127 versions of “Winter Landscape with Ice Skaters and Bird Trap.”

The monographs saught to differentiate autograph works created by Bruehgel the Younger from works primarily by the hands of the many assistents employed in his workshop. Ertz also noted works that were signed and dated.

His greatest impact on the art market was his authentication of works from the Bruehgel family for auction houses like Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Koller and others. The auction houses to bring some level of order to the, if not quite chaos, certainly unclear authorship, of Brueghel’s works. According to a fascinating study (“The Implicit Value of Arts Experts: The Case of Klaus Ertz and Pieter Brueghel the Younger,” Anne-Sophie Radermecker, Victor A. Ginsburgh and Denni Tommasi, January 2017, SSRN Electronic Journal), an Ertz authentication of a work by Pieter Brueghel the Younger increased the work’s value by 60%. While the authentication documents that Ertz created for auction houses were typically short in length, their impact added hundred of thousands of dollars to the sale price of Brueghel-related works. Ertz and the auction houses seemed to have a symbiotic, and very mutually beneficial, relationship.

How Ertz’s death will impact the auction houses, as they will inevitably continue to sell works by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, is an open question. In the brief time since Ertz’s death, only one auction with a Pieter Brueghel the Younger work has been announced (as far as we can ascertain). The work, “The Adoration of the Magi,” was authenticated by Ertz in 2009. Because Ertz authenticated such a large number of paintings during his lifetime, if the owners / auction houses can produce Ertz’s previously created authentication letters, many works will be continue to be sold as verified by Ertz.

Since Ertz began producing his volumes some 40 years ago, many changes have occurred with connoisseurship, catalog raisonnés and their definition and creation. Unsurprisingly, cataloging artist’s works have moved online. For example, a wonderful Jan Brueghel the Elder compendium has been created and overseen by Elizabeth Alice Honig, Professor, University of Maryland, and her team at http://janbrueghel.net/.

As recounted in the Radermecker, Ginsburgh and Tommasi article, expertise in the form of purely visual connoisseurship that Ertz provided has been supplanted by evidence-based technical analysis of the kind applied to the Bruegel family in the groundbreaking volume “The Brueg(H)el Phenomenon: Paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Pieter Brueghel the Younger” by Christina Currie and Dominique Allart. This is because technical analysis provides stronger grounds for securing authorship than a simple visual review of a painting. However, detailed technical analysis is much more time consuming and expensive, making the proposition of technical analysis becoming commonplace at auction houses unlikely in the short term. How art market authentication of the Brueghel family’s works moves forward in the wake Ertz’s death has yet to be seen.

Book Review: Anonymous Art at Auction

The Reception of Early Flemish Paintings in the Western Art Market (1946–2015) by Anne-Sophie V. Radermecker

“What’s in a name?” Not in the Romeo and Juliet sense, but in terms of old master paintings, we know that an artist’s name is inextricably tied to a work’s market value. A work authenticated as painted by “Pieter Brueghel the Younger” commands a massive premium compared to a work whose authorship is listed as “after Pieter Brueghel the Younger” or “school of Pieter Brueghel the Younger.”

But when a work of art cannot be definitively tied to an artist, are there factors of an anonymous painting that impacts the price the work can command in the marketplace? This question is explored in a fascinating new volume, “Anonymous Art at Auction: The Reception of Early Flemish Paintings in the Western Art Market (1946 – 2015),” by Anne-Sophie V. Radermecker (Brill, 2021). This is a must-read for those who want to better understand the features that impact the market value of anonymous Flemish art.

Radermecker was a co-author of a 2017 article, “The Value Added by Arts Experts: The Case of Klaus Ertz and Pieter Brueghel the Younger,” which researched the impact of an art expert’s opinion on the market price for Brueghel the Younger’s paintings at auction. The authors concluded that when Klaus Ertz, the author of Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s catalog raisonne, provided authentication for a Brueghel work, it had a meaningful impact on the price paid. Buyers paid roughly 60 percent more for works authenticated by Klaus Ertz than works without authentication.

Radermecker’s current monograph makes clear from the outset that an artist’s name is the equivalent of a “brand.” But what about the thousands of paintings for which the artist in unknown? The book details the market reception of indirect names, provisional names, and spatiotemporal designations, which are identification strategies that experts and art historians have developed to overcome anonymity.

Building a brand name during an artist’s lifetime was clearly important, conveying three key attributes: recognition, reputation, and popularity. But because many paintings were not signed, the scholarly community used stand-in authorship titles for works that were painted by the same artist or studio.

These stand-ins for names act as identifiers and play a role in determining a work’s economic value. Example of stand-ins for names include “Master of the female Half-Lengths,” “Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy,” and “Master of the Prado Redemption.” This volume points out that value increases when works are ascribed to a painter, in the form of a stand-in name, when the true author’s name is not known.

By ascribing identities for works without named authors, authorship uncertainty is reduced, and new, alternative brands are created. The reduction of authorship uncertainty leads a buyer to feel more confidence in a work, which adds to buyer’s willingness to pay higher prices. Interestingly, the author suggests that the somewhat haphazard nature of application of name labels over the period of the study (1946 – 2015) was a stumbling block that diminished the efficacy of labels.

The author defines a broad set of stakeholders, including art historians, experts, curators, restorers, dealers, etc., who are involved in proposing and establishing names for otherwise anonymous artists. The author makes the point that while the motives of parties from the scholarly field are not theoretically commercial in nature, they must understand their considerable impact on the market.

Further, Radermecker makes the case for the impact of the scholarly field when ascribing certain works as “significant” or disparaging works by referring to their authors as “minor masters” or “pale copyists.” The role of museums as authorities is discussed in the context of historicizing and legitimizing artistic output. The author argues that museums can place artist brands as well as anonymous artist in context and help the general public understand the value conveyed by artist brands.

The book details the curious fact that an objectively lower-quality work linked to a known artist (and their brand) can command significantly higher price than a higher-quality work that is not connected with secure authorship or artist brand.

Further complicating authorship is the very real studio environment in which Netherlandish artists worked. The old master as a “lonely genius” which solely created paintings is a very nineteenth-century notion and colors the market still today. Research conducted over the past 50 years has shown that most artists did not work alone but were frequently part of a larger workshop. The attribution of many paintings continues to be given to a sole artist when the actual participation of the artist and their workshop often varied greatly.

A case is made for anonymous works providing an alternative artistic experience than those of brand name artists. Without artist’s names, the viewer (and potential buyer) focuses on the physical object and its properties in order to provide an option on the work, which then leads to a value determination.

In an intriguing chapter titled “Paintings without Names,” the market reception of painting that lack all nominal designations was analyzed. A sample of 1,578 auction sales results were put through regression analysis, with the finding that works labeled “Netherlandish” were, on average, 22.6% more expensive than works labeled “Flemish.” Further, works that contain the names of locations where major masters settled and created their work also led to higher valuations. Specifically, works labeled “Antwerp” and “Bruges” commanded +30.6% and +59.2% higher prices. The author concludes that these city names not only function as a location of origin, but also as a label of quality related to the artistic hub.

The author has created a nomenclature made up of eight designations that each had a different impact upon sale price, depending on the specificity of the information provided. Designations specifying a work’s location of production led to prices that are higher on average, as noted above. The author also found that 3 other factors were correlated with higher prices – the work’s state of preservation, the length of catalog notes (which in theory correlate to an expert’s potential involvement) and the mention of earlier attributions.

Radermecker‘s thorough analysis and thought-provoking conclusions provide stakeholders (particularly auction houses) with valuable information to leverage when working to maximize the price paid for anonymous artworks.

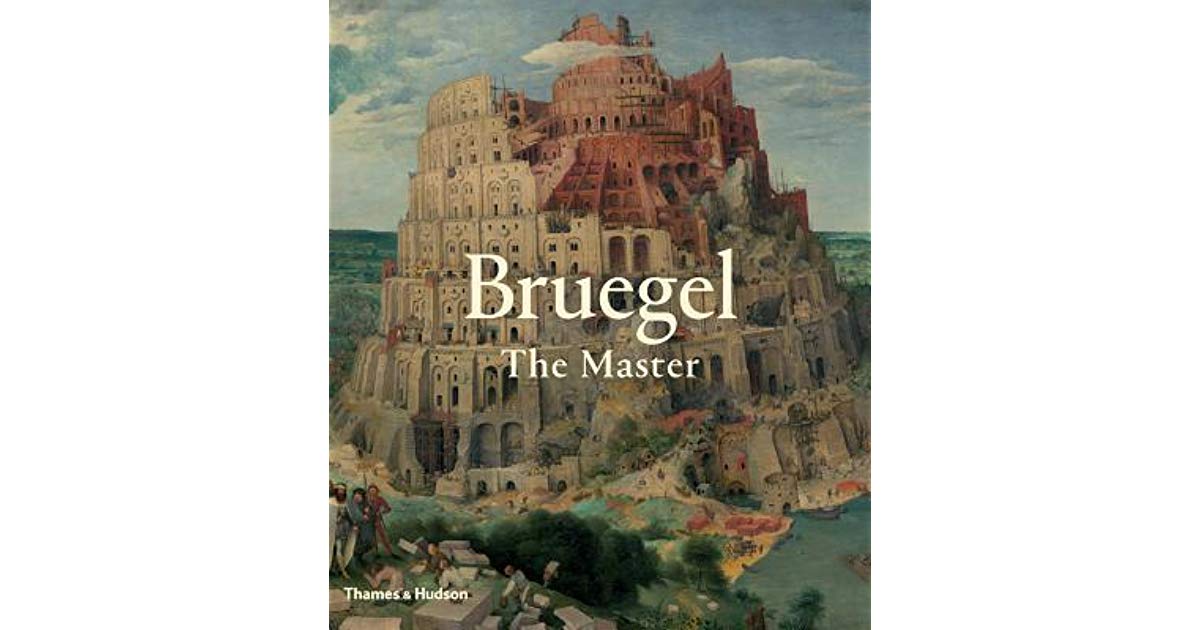

Bruegel The Master: A Crucial New Monograph

The new monograph, Bruegel The Master, published by Thames & Hudson, is a highly engaging tour through Pieter Bruegel The Elder’s print and painting oeuvre. Published in conjunction with the recently concluded exhibition in Vienna, the monograph details Bruegel’s corpus of prints and paintings. Best of all, the monograph includes recent research into Bruegel’s painting techniques undertaken in advance of the Vienna exhibition.

Many Bruegel monographs divide his output by format, with separate sections on his prints and paintings. Bruegel The Master instead weaves both print and paintings together in a roughly chronological review of his output, while delving into the fascinating process undertaken by Bruegel to create his masterpieces. The monograph details Bruegel’s painting techniques, which differed greatly between works. For example, his earlier painted works, such as Children’s Games, The Battle Between Carnival and Lent and Christ Carrying the Cross, have precise, mechanical figure contours, suggesting the transfer of image using a cartoon. In contract, Bruegel’s later works, such as his series of the months (which include The Return of the Heard and The Gloomy Day), have loose and sketchy underdrawings. For these later works, Bruegel’s painting process could only have been possible by preparing a precise conception of the painting prior to beginning his work.

One of the biggest revelations in Bruegel the Master is that many of his paintings were cut down from their original size. Such well-known works as The Suicide of Saul, The Tower of Babel, and The Conversion of Saul are specific examples of works that were altered. The reason for their being cut down remains an intriguing mystery yet to be solved.

The monograph is rife with comparisons, using infrared reflectograms, between the final painting and the preparatory under drawing. This analysis draws the reader into the book and asks them to study the images carefully. For example, a corpse visible in the under drawing of Children’s Games is covered by paint in the final paint layer, as are two children lying on the ground in front of a church, which was also overpainted.

Several works were cleaned in preparation for the exhibit. Some of the cleaning, such as for The Suicide of Saul, is dramatically presented in the book, shown mid-cleaning.

There are five additional essays available online that can be unlocked with a code found in the monograph. These essays take a deeper dive into aspects of Bruegel’s art, including Bruegel’s creative process, his painting materials and techniques, and the history of the works now in Vienna.

It would be nearly impossible for those interested in early Renaissance art history not to be thoroughly engaged by this monograph, as it engages readers in both new historical findings and timeless Bruegelian imagery.

This monograph is an indispensable addition to Bruegel art historical literature.

Event Preview – “The Bruegel Success Story,” 12-14 September 2018

We were fortunate enough to obtain an exclusive preview of the upcoming event, “The Bruegel Success Story,” to be held 12-14 September 2018 in Brussels, Belgium. (http://conf.kikirpa.be/bruegel2018/) This can’t-miss conference kicks off a number of activities celebrating the life and work of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, who died 450 years ago. We corresponded with one of the conference organizers, Dr. Christina Currie, Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA), who gave us this exciting preview of the conference:

1) What led to focusing on Bruegel and his family for this conference?

The year 2019 is the 450th anniversary of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s death. In Belgium and in Vienna, this is being marked by a series of events that will celebrate his career and his influence on later generations. The Bruegel Success Story conference, organised by the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA) in collaboration with the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Belgium, will kick off this season of activities and will give a riveting context for all the subsequent Bruegel themed happenings.

2) What will attendees of the conference learn?

Attendees will be exposed to the very latest in Bruegel research through the eyes of experts from all around the world. Eminent keynote speakers Leen Huet (Belgium), Elizabeth Honig (USA) and Matt Kavaler (Canada) will introduce each of the three days. Over the course of the conference, presentations will cover the life and work of Pieter Bruegel the Elder as well as that of his artistic progeny, including the astonishingly exact replicas of his paintings produced by his elder son Pieter Brueghel the Younger and the exquisite paintings of his younger son Jan Brueghel the Elder. Fascinating new findings on the creative process of Bruegel the Elder as well as that of his dynasty will be presented for the first time, thanks to new high resolution scientific imagery. But the conference does not neglect the essential meaning behind these beautiful works of art. Several speakers will concentrate specifically on the interpretation of Bruegel’s paintings and drawings, which can be quite subversive when seen in an historical context. Interesting new facts about the life, family and homes of the Bruegel family will also be revealed.

3) Who should attend this conference?

The Bruegel Success Story is intended for all art lovers with an interest in Flemish painting and particularly those attracted to Bruegelian themes such as peasant dances, landscapes, proverbs and maniacal scenes. Students of art history, art historians, restorers and collectors should not pass up this opportunity.

3) There are a number of papers focusing on Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting “Dulle Griet.” Why is that painting receiving attention now?

The Dulle Griet, in the collection of the Mayer van den Bergh Museum in Antwerp, has just undergone the most thorough conservation treatment in its recent history. This has brought to light many original features that were previously hidden behind a murky brown varnish and overpaint. The restoration, carried out at the Royal Institute for Cultural Institute in Brussels, was accompanied by in-depth technical examination that resulted in fascinating discoveries about Bruegel the Elder’s creative process. The conference attendees will hear how this great artist conceived, developed and painted this bizarre macabre composition. Leen Huet, one of the keynote speakers and author of a sensational recent biography on Bruegel the Elder, will delve into the hidden meaning behind the Dulle Griet.

4) One of the biggest bombshells in recent years was the revelation in your book (“The Brueg(h)el Phenomenon”) that Bruegel the Elder’s two versions of “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” were not painted by Bruegel the Elder. Will there be similar surprises unveiled at the conference?

I can say that attributions will be debated during the conference. This is always the case when a group of experts on a particular artist or dynasty get together. And it can lead to sparks flying as opinions naturally diverge!

5) There has also been a good deal of investigation into Bruegel’s extended family lately. What will attendees learn about Bruegel’s family at the conference?

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s paintings were so loved that his son and heir Pieter Brueghel the Younger made his entire career out of producing replicas for an insatiable art market in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century. Jan Brueghel, his younger brother, updated the family tradition, branching out into flower paintings, allegories and mythological themes. The next generation produced several renowned painters too, including Abraham Brueghel, who traded on the family name. The paintings of the Bruegel dynasty, as well as those of lesser-known artists working in the Bruegel tradition in the Low Countries and abroad, will feature amongst the exciting new material presented during the conference.

The Bruegel Success Story symposium – September 12 – 14, 2018, Brussels

A blockbuster conference containing the latest research on the Bruegel / Brueghel family of painters is being held this fall in Brussels. Many of the leading Bruegel scholars are presenting new findings related to the Bruegel dynasty.

Discoveries related to the Bruegel clan – including patriarch Pieter the Elder, sons Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Jan Brueghel the Elder and other members of the family – will be presented at the symposium. One of the highlights will be presentations related to Pieter Bruegel’s “Dulle Griet,” a painting in Antwerp which has recently undergone extensive investigation, research and cleaning.

The Bruegel / Brueghel clan continues to be top draws at museums and set records at auction (including toping high estimates at this week’s Old Master’s auctions in London).

Registration is open now for this impressive symposium.

More information and registration at http://conf.kikirpa.be/bruegel2018/.

————————————————————————–

Conference Venue: Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Place du Musée, B-1000 Brussels.

THE PROGRAM

12 September 2018, WEDNESDAY

9:00 – 9:45 Registration at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

9:45 – 10:00 Welcome by Hilde De Clercq, director of the KIK-IRPA and Michel Draguet, director of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

CHAIR Lieve Watteeuw

10:00 – 10:40 KEYNOTE LECTURE: Leen Huet, The Surprises of Dulle Griet

10:40 – 11:00 Larry Silver, Sibling Rivalry: Jan Brueghel’s Rediscovered Early Crucifixion

11:00 – 11:20 Véronique Bücken, The Adoration of the Kings in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium: Overview and new perspectives

11:20 – 11:30 Discussion

COFFEE BREAK 11:30 – 12:00

CHAIR Dominique Allart

12:00 – 12:20 Yao-Fen You, Ellen Hanspach-Bernal, Christina Bisulca and Aaron Steele, The Afterlife of the Detroit Wedding Dance: Visual Reception, Alterations and Reinterpretation

12:20 – 12:40 Manfred Sellink, Marie Postec and Pascale Fraiture, Dancing with the bride – a little studied copy after Bruegel the Elder

12.40 – 13.00 Mirjam Neumeister and Eva Ortner, Examination of the Brueghel holdings in the Alte Pinakothek/Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich

13:00 – 13:10 Discussion

LUNCH BREAK 13:10 – 14:30

CHAIR Elizabeth Honig

14:30 – 14:50 Amy Orrock, Jan Brueghel the Elder’s Oil Sketches of Animals and Birds: Form, Function and Additions to the Oeuvre

14:50 – 15:10 René Lommez Gomes, Regarding the Character of Each Animal. An essay on form and colour in non-European fauna painted by Jan Brueghel the Elder

15:10 – 15:30 Uta Neidhardt, The Master of the Dresden “Landscape with the Continence of Scipio” – a journeyman in the studio of Jan Brueghel the Elder?

15:30 – 15:40 Discussion

COFFEE BREAK 15:40 – 16:10

CHAIR Bart Fransen

16.10 – 17.10 Christina Currie, Steven Saverwyns, Livia Depuydt, Pascale Fraiture, Jean-Albert Glatigny and Alexia Coudray, Lifting the veil: The Dulle Griet rediscovered through conservation, scientific imagery and analysis

Christina Currie, Steven Saverwyns, Sonja Brink, Dominique Allart, The coloured drawing of the Dulle Griet in the Kunstpalast, Dusseldorf: new findings on its status and dating

Dominique Allart and Christina Currie, Bruegel’s painting technique reappraised through the Dulle Griet

17:10 – 17:20 Discussion

18.00 Opening reception in Brussels Town Hall (Gothic and Marriage rooms)

13 September 2018, THURSDAY

9:00 Doors open

CHAIR Ethan Matt Kavaler

9:30 – 10:10 KEYNOTE LECTURE: Elizabeth Honig, Copia: Jan Brueghel and the Rhetoric and Practice of Abundance

10:10 – 10:30 Yoko Mori, Is Bruegel’s Sleeping Peasant an Image of Caricature?

10:30 – 10:50 Jamie Edwards, Erasmus’s De Copia and Bruegel the Elder’s ‘inverted’ Carrying of the Cross (1564): An ‘abundant style’ in Rhetoric, Literature and Art?

10:50 – 11:00 Discussion

COFFEE BREAK 11:00 – 11:30

CHAIR Leen Huet

11:30 – 11:50 Tine Meganck, Behind Bruegel: how “close viewing” may reveal original ownership

11:50 – 12:10 Annick Born, Behind the scenes in Pieter Bruegel’s success story: the network of the in-laws and their relatives

12:10 – 12:30 Petra Maclot, In Search of the Bruegel’s Homes and Workshops in Antwerp

12:30 – 12:40 Discussion

LUNCH BREAK 12:40 – 14:40

CHAIR Christina Currie

14:40 – 15:00 Lieve Watteeuw, Marina Van Bos, Joris Van Grieken and Maarten Bassens, ‘View on the Street of Messina’, circle of Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Drawing techniques and materials examined

15:00 – 15:20 Maarten Bassens, “Diet wel aenmerct, die siet groot wondere”. Retracing Pieter Bruegel’s printing press(es) by means of a typographical inquiry

15:20 – 15:40 Edward Wouk, Pieter Bruegel’s Subversive Drawings

15:40 – 15:50 Discussion

COFFEE BREAK 15:50 – 16:20

CHAIR Valentine Henderiks

16:20 – 16:40 Jürgen Muller, Pieter Bruegel’s “The Triumph of Death” revisited

16:40 – 17:00 Jan Muylle, A lost painting of Pieter Bruegel, The Hoy

17:00 – 17:20 Hilde Cuvelier, Max J. Friedländer’s perception of Bruegel: Rereading the connoisseur with historical perspective

17:20 – 17:30 Discussion

14 September 2018, FRIDAY

9.00 Doors open

CHAIR Manfred Sellink

9:30 – 10:10 KEYNOTE LECTURE: Ethan Matt Kavaler, Peasant Bruegel and his Aftermath

10:10 – 10:30 Christina Currie and Dominique Allart, The creative process in the Triumph of Death by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and creative solutions in two versions by his sons

10:30 – 10:50 Anne Haack Christensen, David Buti, Arie Pappot, Eva de la Fuente Pedersen and Jørgen Wadum, The father, the son, the followers: Six Brueg(h)els in Copenhagen examined

10:50 – 11:00 Discussion

COFFEE BREAK 11:00 – 11:30

CHAIR Dominique Vanwijnsberghe

11:30 – 11:50 Lorne Campbell, Bruegel and Beuckelaer: contacts and contrasts

11:50 – 12:10 Patrick Le Chanu, Pieter Bruegel the Elder and France

12:10 – 12:30 Daan van Heesch, Hercules et simia: the Peculiar Afterlife of Bruegel in Sixteenth-Century Segovia

12:30 – 12:50 Francesco Ruvolo, The Painter and the Prince. Abraham Brueghel and Don Antonio Ruffo. Artistic and cultural relations in Messina from the seventeenth century. With unpublished documents

12:50 – 13:00 Discussion

LUNCH BREAK 13:00 – 14:30

CHAIR Véronique Bücken

14.30 – 14.50 Lucinda Timmermans, Painted ‘teljoren’ by the Bruegel family

14:50 – 15:10 Pascale Fraiture and Ian Tyers, Dendrochronology and the Bruegel dynasty

15:10 – 15:30 Jørgen Wadum and Ingrid Moortgat, An enigmatic panel maker from Antwerp and his supply to the Brueghels

15:30 – 15:50 Ron Spronk, Elke Oberthaler, Sabine Pénot, and Manfred Sellink, with Alice Hoppe Harnoncourt, The Two Towers: Pieter Bruegel’s Tower of Babel panels in Vienna and Rotterdam

15:50 – 16.00 Discussion

16:00 – 16:10 Closing Remarks: Christina Currie and Dominque Allart

Exhibit Review – Bruegel: Defining A Dynasty

Several weeks ago I wrote about the catalog for the exhibit Bruegel Defining a Dynasty by Amy Orrock. Now, having seen the exhibit firsthand, I can confirm what I suspected after reading the catalog; that the exhibit, presented by outgoing museum director Jennifer Scott, is a marvelous exploration of the Bruegel family brought vividly to life.

Smartly, the exhibit begins with an overview of the Bruegel family tree, showing the relations of family members whose paintings will be viewed in the coming rooms.

A work from the genius at the top of the family tree, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, greets us as we enter the first room. The Adoration of the Kings, 1564, is Bruegel at his finest, a visual feast for the eyes along with not-subtle commentary that reflects how some on-lookers appeared to be more interested in the gifts brought for Christ than the child himself.

One of the exhibition’s aims was to show that Pieter the Elder’s two male children, Pieter the Younger and Jan the Elder, were not simply copyists, but added their own personalities to scenes that their father first painted. Comparing Jan the Elder’s version of The Adoration of the Kings, for example, is a wonderful example of how Jan adjusted and enhanced his father’s composition, by adding elements like a town in the background and details of the dilapidated stable where the scene is set.

The Bruegel exhibit also showcases works painted outside of the family, such as the version of Netherlandish Proverbs included here. This work is intriguing because it omits one fourth of the proverbs found in Bruegel the Elder’s painting. Further, it is much smaller than the copies made by Pieter the Younger and his studio, and does not contain the characteristic underdrawing found in Pieter the Younger’s works. Scientific analysis indicates that it was produced at approximately the same time as the works by Pieter the Younger’s studio in the early seventeenth century. However, this work contains aspects of the completed Bruegel the Elder painting that are not included in Pieter the Younger’s copies. This means that while Bruegel the Younger did not have access to his father’s completed painting, the painter of this work did have access. How non-family members could have accessed the painting is just one of the mysteries discussed in the exhibit.

Family members showed their expertise with other genres such as still lifes, which Jan the Elder and Jan the Younger were undisputed masters. Jan Brueghel the Elder’s grandson, Jan van Kessel, is represented in four small paintings that depict insects set against a light background. The pictures gleam through the copper substructure, with the insects painted in minute detail.

There are many mysteries still to be solved within the family, such as what was Pieter Bruegel III’s role in his father Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s workshop. Exhibits like this one allow us to revel in the depth and breadth of the family’s output, and consider the many mysteries still be examined.

(Bruegel: Defining a Dynasty at the Holburne Museum, Bath, England, February 11 – June 4, 2017 £10 Full Price | £9 concessions | £5 Art Fund, Full Time Student | FREE Entry to under 16s and All Museum Members)

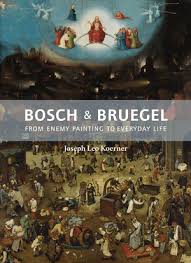

Bosch and Bruegel: From Enemy Painting to Everyday Life

Bosch and Bruegel: From Enemy Painting to Everyday Life

By Joseph Leo Koerner

Princeton University Press, 2016

Koerner’s beautifully illustrated book focuses on the rise of secular European art after centuries’ of religious-themed works. He chronicles the growth of secular painting, which later became known as “genre painting,” or works which portray everyday European life. Koerner’s thesis is that the transition to secular painting had its roots in Bosch’s depictions of demons and phantasmagoric creatures, which were representations of human weakness and sin (referred to as “enemy painting”). Bruegel’s paintings, 50 years after Bosch, also contained “undesirable” images, but instead of fantastic creatures, Bruegel focused on human foolishness in his depictions of peasants dancing and other imprudent antics.

Koerner constructs a compelling argument for this thesis, which is greatly enhanced by the book’s abundant images from both Bosch and Bruegel’s paintings. Koerner demonstrates that surviving paintings by both artists show a commonality of subjects; demons, fools, and knaves (“gluttons, lazybones, drunkards, dupes, thieves, bullies, charlatans and quacks”). Lost paintings by Bosch also included subjects that are now closely associated with Bruegel, including “peasant dances and peasant weddings, a huge Battle between Carnival and Lent, a Tower of Babylon, a feast of Saint Martin and works on linen of beggars, merrymakers” and others. As Koerner notes, Bosch appears to have painted nearly all of the subjects now typically associated with European genre painting.

Not only was Bosch and Bruegel’s subject matter similar, but the gestalt of the paintings were also parallel. A bird’s-eye point of view is common to both artist’s compositions. In addition, Bosch and Bruegel filled their works with richly detailed, intricate figures. Their paintings overload our senses with characters and figures that seem to stretch far beyond the limits of the physical works. Further to the similarity of the two artist’s paintings, Koerner points out that until fairly recently, major works by Bruegel were attributed to Bosch, including “The Triumph of Death” in the Prado and “The Fall of The Rebel Angels” in Brussels.

Bosch and Bruegel’s painterly styles were similar too, in that both artists allowed the ground paint layer to penetrate the upper paint layer in certain sections, contributing to the final look of the pictures.

Koerner connects the two artists via their patrons as well. Both were sought out by the elite of their day, including high-ranking politicians and famous humanists. Bosch and Bruegel frequently signed their works, which was not typical of artists of this time period (with the exception of Jan van Eyck).

Koerner spends equal time discussing the artist’s differences as well, stating that “no one makes Bosch seem more historically remote than does Bruegel.” With Bosch, the enemy is the Devil and sin, while Bruegel demonstrated that “genuine evil flourishes in the activity of ordinary people.”

The second two-thirds of the book are comprised of detailed sections relating the life and artistic output of first Bosch, then Bruegel. Koerner reviews key works from both artists and how these works fit into the themes of the book. For Bosch, Koerner zeros in on The Garden of Earthly Delights, which to this day continues to baffle viewers trying to “crack the code” of this enigmatic work. In a later chapter Koerner focuses on Bruegel’s The Magpie on the Gallows, tying this work back to Bosch’s heaven and hell imagery, with peasants dancing beneath the gallows.

Koerner convincingly links Bosch and Bruegel together as the originators of “genre scenes” and brings a fresh perspective to both artist’s works, tying them to the larger context of subsequent European paintings. This book is an excellent addition to both Bosch and Bruegel scholarship, leaving the reader with an even greater admiration of these two towering artist’s talents.

Bruegel’s Children’s Games – A Curious (Old) Copy Has Just Surfaced

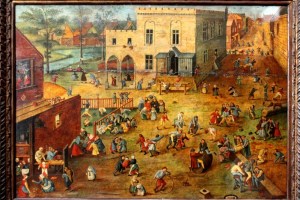

Recently we’ve been given the opportunity to examine first hand a very interesting copy of Bruegel’s Children’s Games. The painting is large – 28″ X 39″, seemingly painted on a single panel (or two panels), potentially painted on larch (birch).

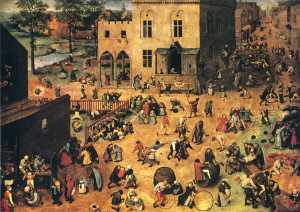

Below is the original version from 1560

Below is the copy from ?

What makes this copy so interesting is how it diverges from Bruegel’s original. There are many Children’s games that are missing from the copy, as seen in the illustrations below.

Figures that appear in both versions are in yellow. Those not highlighted are missing from the curious copy:

This blog will document the research done on this painting to ascertain when it was painted, and potentially who painted it.

We love a detective hunt!