BruegelNow

Bruegel

Bruegel: Defining a Dynasty

Bruegel: Defining a Dynasty by Amy Orrock (Philip Wilson Publishers, 2017). Published to accompany the exhibition Bruegel: Defining a Dynasty (11 February – 4 June, 2017) at the Holburne Museum, Bath, UK.

Perhaps the best known dynasty in the history of painters, the Bruegel family flourished for nearly 150 years. This book, written in conjunction with an exhibit that showcases the depth and breadth of the Bruegel clan, provides a history of the family along with visually dazzling key works.

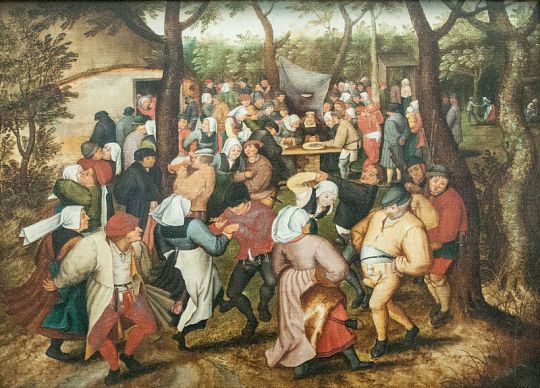

The centerpiece of the book is the section that details the attribution of The Wedding Dance in the Open Air to Pieter Brueghel the Younger. The “heavy dancers” depicted in the painting are some of the best known figures of Bruegel’s oeuvre. Yet this painting was originally thought to be a copy by a follower of Brueghel the Younger.

Key to the attribution was the cleaning of the painting. The pre- and post-conservation images portray a drastically different work. Before conservation the work looked like a nocturnal scene, covered in layers of discolored varnish and numerous retouching. The restoration, carried out by Elizabeth Holford, led to a greatly lightened, visually stunning painting.

Christina Currie and Dominique Allart, who wrote the definitive scientific examination of Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s output several years ago, examined the work and secured its attributed to the artist. They studied the painting’s underdrawing, which conformed to paintings typical of Pieter Brueghel the Younger. They concluded that he work “… equals that found in the other versions studied, signifying that it belongs within” the Brueghel the Younger group.

This monograph successfully demonstrates that the Bruegel family wasn’t only a painter of dancing peasants. For example, Pieter’s younger brother, Jan Brueghel the Elder, created beautiful still life paintings. Unlike his brother, Jan collaborated extensively with other painters. Over 40 percent of his painted output consists of collaborate works. The friend of Rubens and Van Dyke, Jan the Elder’s works sold for 10 or 20 times the price of his older brother’s works. (A situation that has reversed itself in the late 20th and 21st century, where Pieter’s works sell for many millions while Jan’s works are available at a much lower sum.)

Jan Brueghel the Elder’s grandson, Jan van Kessel, excelled in small paintings of “naturalia,” which mimicked insect and other types of animal specimen that were difficult or impossible to obtain. Highlighted in the book are four small paintings on copper panels that depict native insects against light backgrounds.

This highly recommended book not only provides a wonderful overview of the Bruegel family, but also made me want to immediately rush to the Holburne museum to see the paintings in person. (I will have to wait a few weeks until I am able to do this.)

Searching for Niclaes Jongelinck’s House

One of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s greatest patrons was Niclaes Jongelinck, who owned 16 of his paintings. The paintings were hung at Niclaes Jongelinck’s villa, called ‘Hof Ter Beke’, which was then located outside of the city walls of Antwerp.

Sadly, Niclaes Jongelinck’s house is no longer standing. As I was preparing for a trip to Antwerp, I thought it would be interesting to attempt to locate where his house would have stood in present-day Antwerp. I set about trying to locate his house in the hustle and bustle of modern-day Antwerp.

I enlisted the staff at Antwerp’s Urban Planning, Archaeology and Monuments Department in helping me pinpoint the exact location where his house would have stood. The Antwerp team indicated that it was very difficult to locate the exact position of the original building on a present day map as displayed on 17th century maps. The old maps do not have the necessary precision to use them in a computer geographical information system (GIS). However, as you will read, they did provide remarkable insight into the likely location of the house.

The Antwerp team reported that one author, Rutger Tijs, indicated that the house of Jongelinck is located between the Hof Ter Bekestraat, Sint-Laureisstraat, Haantjeslei and Pyckestraat. According to Van Weghe, in 1885 the then-opened Moonstraat ran across the estate, which the Antwerp team thinks is the last ‘Hof Ter Beke’. (The current site is industrial buildings.) The Antwerp team investigated the site in 2005, but did not find the remains of structures older than the early 20th century.

Others also investigated the likely location of Niclaes Jongelinck’s house. The Antwerp team reported that Plomteux, Prims and Vande Weghe stated that the site where the villa owned by Niclaes Jongelinck once stood can be located between the current streets Hof Ter Bekestraat, Broederminstraat, Lange Elzenstraat and Oudekerkstraat. The Antwerp team agrees with this conclusion and indicate that on the maps of 1617 and 1624 the Jonckelinck villa is clearly shown on the south side of the present day Markgravelei while the other possible location (cf. Rutger Tijs) is clearly indicated on the north side.

According to Vande Weghe, in 1872 a new street called the Jongelincxstraat was opened on the estate witch was then owned by the Van den Broeck family. Prior to their ownership, Madam Schul was the owner. Further, in 1873 a new street, the Coebergerstraat, was opened on the estate. According to the Antwerp team this portion was owned by Van Put and Wilmotte.

The Antwerp team says that it does not seem likely that any of the original buildings survived. According to the list with building permits held at the City Archives, the area was built up in a short period of time from 1872 onward. The largest part of these houses are one family residential buildings dating from 1872 forward.

Niclaes Jongelinck’s villa (indicated on maps in 1617 and 1624 but not on the map from 1698) or at least a building which it replaced is drawn on the 1802 and 1814 cadastral drawings. On the 1836 drawing it is not present. The Antwerp team assumes that it was demolished somewhere between 1814 and 1836. When the Antwerp team tried to project the 1814 drawing on a geographical information system present day map, it seems that the buildings location is under or in the neighborhood of the present day building Coebergerstraat 35-37. The team indicates that the precision of this location is as good as the precision of the 1814 map and the number of comparison points they found. Thus, they conclude that an error of a few meters, but not more, is possible.

The map that you can see below shows a portion of the 1814 map with the current map imprinted on it in red. The two above mentioned places are marked with a purple circle. (You can download the PDF by clicking on the “Villa with current map” link below.)

So, for those going to Antwerp, we at Bruegelnow.com recommend a visit to Coebergerstraat 35-37!

Here is a current view of Coebergerstraat 35-37

————————————————————————–

Many thanks to Georges Troupin, technisch bestuursassistent, Stad Antwerpen, Stadsontwikkeling, archeologie, monumenten- en welstandszorg, for his substantial assistance solving this puzzle!

The following literature was quoted:

Greet Bedeer en Luc Janssens, Steden in beeld, Antwerpen, 1200-1800, Brussel 1993

Guido De Brabander, Na-kaarten over Antwerpen, Brugge 1988

G. Plomteux G. & R. Steyaert met medewerking van L. Wylleman, Inventaris van het cultuurbezit in België, Architectuur, Stad Antwerpen, Bouwen door de eeuwen heen in Vlaanderen 3NC, 1989 Brussel – Turnhout.

Floris Prims, De littekens van Antwerpen, Antwerpen 1930

Floris Prims en H. Fierckx, Atlas der Antwerpsche Stadsbuitenijen van 1698, Anterpen 1933

Rutger Tijs, de twaalfmaandencyclus over het leven van Pieter Bruegel als interieurdecoratie voor het huis van plaisantie ‘ter Beken’ te Antwerpen. in J. Veeckman (red.) Berichten en Rapporten over het Antwerps Bodemonderzoek en Monumentenzorg 3, Antwerpen 1999, p. 117-133.

Roberd Vande Weghe, Geschiedenis van de Antwerpse straatnamen. Antwerpen 1977.

Cartographic sources are below:

Marchionatus Sacri Romani Imperii, in P.Keerius, La Germanie Inférieure.1617 Library UFSIA

Marchionatus Sacri Romani Imperii, Claes Janszoon Visscher 1624 City Archive

Dubray, Plan du territoire de la ville d’Anvers divisé en 5 sections, levé géométriquement par Dubray arpenteur géographe du Depart[ement] des 2 Nethes en l’an X 1802, City Archive 12#3944

Dubray en J. Witdoeck, Plan de la cinquième section IIIeme partie lévé géométriquement par Dubray arpenteur géographe du Departement des Deux Nethes en l’an X”; “Renvoi indicatif du supplement des parties qui ont été fait au plan d’après l’Atlas [met legende] fait par moi géomètre soussigné, le supplement à ce plan […] et conformement à l’Atlas du 15 Mars 1812. Anvers, le 21 Decembre 1814, F.D. Witdoeck. 1814 City Archive 12#4270

C.J. Van Lyre, Atlas der Antwerpsche Stadsbuitenijen. 1698. Cf. literature Prims

J. Witdoeck, 5e wijk genaamd extra muros der stad Antwerpen. 1836, City Archive 12#3077

Alouïs Scheepers, Plan géométrique parcellaire et de nivellement de la ville d’Anvers et des communes limitrophes dressé et gravé à l’échelle de 1 à 5000 par Alouis Scheepers conducteur des travaux communaux au service de Monsieur Th. Van Bever, ingénieur de la ville, publié sous les auspices de l’administration communale. 1868. 1868, City Archive 12#8824

Alouïs Scheepers, Plan geometrique parcellaire et de nivellement de la ville d’Anvers et des communes limitrophes dressé et gravé par Aloïs Scheepers, conducteur de travaux communaux au service de monsieur G. Royers, ingénieur de la ville publié sous les auspices de l’administration communale. Edition de 1886. 1886, City Archive 12#12541

“Children’s Games” Variant – What Do We Know?

Over the past few months we have had an opportunity to study an interesting “Children’s Games” variant.

We have studied the infrared reflectography image taken, as well as an X-ray image and several images created with various light and dark shading.

Let’s review the images and discus what they reveal about the painting:

First, this image (below) clearly indicates that the painting is quite dirty through age and discoloration of varnish.

This image (below) with light raking from the right side make clear the few small places on the painting which have been cleaned, so the bright colors of the original panel come through, such as in the upper right corner where the sky has been cleaned and the middle left, where the young girl has been cleaned.

An ultraviolet light image (below) shows clearly some of the damage to the painting that has occurred over the decades. The most pronounced damage is along edge where the first and second panels were joined together. There also is damage in the middle of the painting with a few scratches.

One of the mysteries that we are trying to solve with this analysis is to determine when the painting was created. The image below of raking light on the back of the painting clearly shows that the 3 boards which comprise the painting were created with saw-type tools, and don’t appear to be created by a machine.

A recently published monograph “Frames and supports in 15th- and 16th-century southern netherlandish painting” by Hélène Verougstraete has been instructive in our analysis of the marks on the back of the panel. This has been instructive relative to how the panel was created. While none of the images in the monograph are an exact match, some, such as the figure a (page 33) appear to be somewhat close.

However, we aren’t able to date the panel with certainty based on this information.

The image below clearly shows the repair that panel has undergone, most noticeably the increased support that the panel has had to repair and support the joining of the first two panels, where the damage in the other panels can readily be seen.

We are continuing to examine this panel and look forward to sharing our findings here!

Detective Hunt for a Lost Bruegel

Laurence Smith has conducted interesting research on a “lost” Bruegel work. After viewing a black and white print in “Pierre Bruegel L’Ancien” by Charles de Tolnay (1935) , Smith began doing research on the van der Geest collection that contained the lost work and found a passage in the Phillippe and Francois Roberts-Jones “Pieter Bruegel” (1997) monograph stating:

“ … One of the richest collections in Antwerp in the mid-seventeenth century was that belonging to Peeter Stevens, which contained, besides works by Bruegel, paintings by Van Eyck, Quentin Metsys, Hans Holbein, Rubens, and Van Dyck. A wealthy cloth merchant and city benefactor who gave alms to the poor and was a patron of the arts, he appears in the center of Willem van Haecht’s painting of 1628, The Collection of Cornelis van der Geest. Peeter Stevens also annotated a copy of Van Mander’s Schilder-Boeck with the statement that he had seen twenty-three paintings by Bruegel, of which he possessed a dozen. The catalogue “Of the most renowned Rarities belonging to the late Mr. Peeter Stevens … Which will be sold the thirteenth day of the month of August and the following days of this year 1688, in the House of the deceased” listed: “By Bruegel the elder: A very famous Heath, where peasant men and Women go to market with a cart & a swine, & others”-a lost painting which appears on the left-hand wall in The Collection of Cornelis van der Geest, from whom Stevens had bought it (a drawing with watercolor, in the print room in Munich, also shows the same subject); …”

Was this really a lost Bruegel the Elder painting that now only survives in a watercolor of the collector van der Geest’s paintings?

Smith had the curator of the Rubenshuis Antwerp send him a close up photo of the section of the painting with the Bruegel. The Bruegel is high up on the left hand side and consequently at a steep angle. Smith scanned the photo and attempted to straighten it and pull it into a rectangle. The artist of the watercolor was careful, Smith notes, “to include some detail and seems to have included enough to recognize the wagon and the tree and two or three of the people going to market. The colouring is dark…”

Smith then contacted the print room in Munich and was able to obtain a color print of the watercolor. Smith found that the print had bits of color to distinguish different portions of the print, but it was not very helpful in discerning if the original was by Bruegel the Elder. If the work wasn’t by Bruegel the Elder, could it have been by his son Jan?

Smith studied the work of Jan Brueghel the Elder, and noted that he used the market day subject several times and also included similar images of peasants walking along a path in his other painting. Smith notes that the jug is shown in the watercolor without a hand supporting it, which differs from his other works.

On the question of whether Pieter Bruegel the Elder initiated the design that Jan copied or whether the original in the van de Geest collection should have been attributed to his son, Smith notes that it is impossible to know for certain, but concludes that it appears to be a Jan original rather than that of the elder Bruegel. Based on my knowledge, I would concur with this conclusion as well.

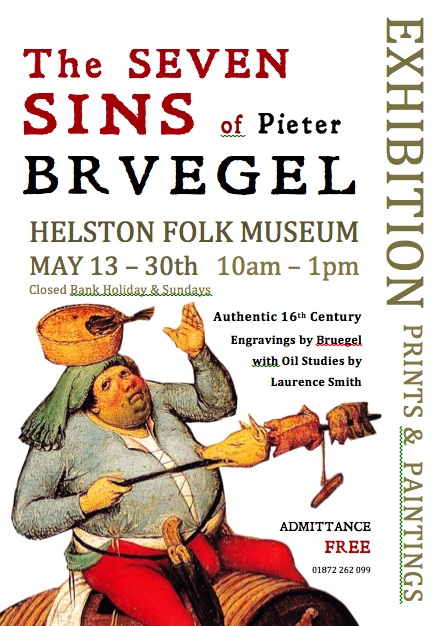

Not only is Smith conducting this type of interesting research, but he also is running an upcoming Bruegel exhibition of a selection of engravings and oil studies. The exhibit, at the Folk Museum at Helston in Cornwall, runs from May 13 – 30, 2013. You can find Smith’s website at http://pieter-bruegel.co.uk

Brueghels In Australia – “Peasant” Wedding Dance” at the University of Melbourne

Currie & Allart’s “The Brueg(h)el Phenomenon” monograph set which I wrote about recently has been an invaluable resource in conducting research about a Pieter Brueghel III painting.

As background, in preparation for a recent trip to Australia, I was interested in determining if any works derived from Bruegel the Elder were to be found on the continent. I learned of a “Peasant Wedding Dance,” attributed to Pieter Brueghel III, in the collection of the University of Melbourne.

According to the University of Melbourne’s catalog entry written by Dr. Jaynie Anderson … “In 1968 Professor Carl de Gruchy bought the work from the Pulitzer Gallery, London, which had bought it from a Dr. J. Henschen of Basel, Switzerland.” Denise de Gruchy gave the work to the University in memory of her brother in 1994. The work is thought to be from the early seventeenth-century (c. 1610), and is 116 X 138.5 cm on canvas. The Melbourne work is neither signed nor dated, and is currently displayed in the Karagheusian Room at University House (see below – “Peasant Wedding Dance” by Pieter Brueghel III, Melbourne Museum of Art Collection.)

I’ve been interested in learning more about Pieter Bruegel III’s paintings, since there is little known about the artist or his works. I’ve uncovered no monographs about him, and scant bibliographic information is available. It seems that Brueghel III was born in 1589 and is said to have first worked in, then later taken over, the workshop of his father, Pieter Brueghel the Younger.

Thanks to Currie & Allart’s detailed description of the painting, I learned that “Wedding Dance in the Open Air” (which has the same figural group as “Peasant Wedding Dance”) was a popular small-format (approx.. 40 cm X 60 cm on panel) work for Brueghel the Younger, with over 100 versions cataloged. The Melbourne version does not appear in Klaus Ertz’s (2000) or Georges Marlier’s (1969) catalogue raisonne of Brueghel the Younger, nor in Currie & Allart.

Most of the Brueghel the Younger compositions of “Wedding Dance in the Open Air” follow the format seen below, which Currie & Allart refer to as a “left handed” orientation (see below: “Wedding Dance in the Open Air” by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Belgium)

However, an engraving after a presumably lost Bruegel the Elder painting as well as copies by Jan Brueghel the Elder and Bruegel’s contemporary Maerten van Cleve show a “right handed” orientation, which is the style of the Melbourne painting. If the Melbourne work is by Brueghel III, then he would have vastly increased the size of the work, reversed the format of his father’s work by painting a “right handed” version, and switched from panel to canvas. I have searched databases listing Brueghel II’s works, and found no other horizontal version of the painting by either Brueghel the Younger or Brueghel III that had a right hand orientation in the small format. (There is one vertical format signed by Pieter the Younger.)

Viewing the painting in person, it is certainly “Bruegelian,” but lacks the subtlety and painterly expertise of the other Pieter the Younger versions. The work is particularly unrefined in certain areas, such as in the middle right section of the work with the men near the tree. Further, the color of the clothing of the dancers in the Brueghel III work differ substantially from the colors in the Brueghel the Younger versions.

It is hoped that an X-radiograph can be created for the Melbourne work, which would provide additional insight. In addition, it would be helpful to view photographs of the reverse of the painting to learn if they would provide further clues regarding the creation of the painting. Finally, since the Brueghel the Younger versions were painted with a cartoon, it would be interesting to examine the work to attempt to determine if a scaled up cartoon was used.

Thanks to Currie & Allart’s monograph, I was able to very quickly do further research into this rare and interesting example of a Bruegel-related work in Australia.

(My gratitude to Dr. Jayne Anderson, Professor, Art History and Robyn Hovey, Collections Manager, The Ian Potter Museum of Art, for their generous assistance discussing and viewing this work.)

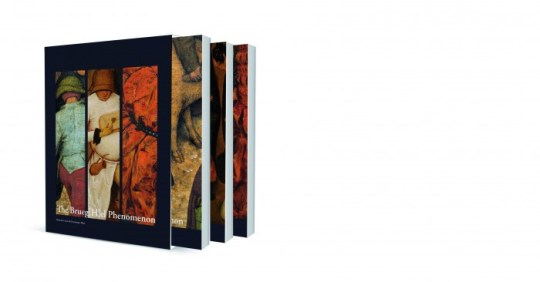

Phenomenal New Book: The Brueg(h)el Phenomenon

The Brueg(h)el Phenomenon

By Christina Currie & Dominique Allart

Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, 2012

This epic, three-volume monograph will likely be seen as a watershed in the study of Bruegel / Breughel works of art. The Bruegel dynasty, begun by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and continued primarily by his son Pieter Brueghel the Younger and then grandson Pieter Brueghel II, has enchanted viewers for hundreds of years. While there have been countless monographs reproducing the Elder Bruegel’s work (and to a much lesser degree, the works of Pieter Brueghel the Younger), technical-stylistic examination of the father and son’s work has not been undertaken until now. This textual inquiry is accompanied by abundant illustrations bring to life the author’s hypothesis about the Brueg(h)el’s work and practices.

The first volume reviews the artistic and cultural milieu in the late sixteenth century in which Bruegel began his career. A review of Bruegel’s work and posthumous fame follow, and while this ground has been well covered in the past, the author bring new insight due to the stylistic focus of their inquiry. Brueghel the Younger’s work is reviewed, along with a review of Brueghel’s likely workshop practices, which continues in the other two volumes. Brueghel the Younger’s long life allowed for a prestigious output of over 1,400 paintings, which necessitated a workshop of significant size.

The meaning of signatures and dates on the works of Bruegel the Elder and Breughel the Younger are discussed in fascinating detail. Why were some works signed, while others were not? Works which are of similar quality are sometimes signed – and sometimes not. Were the signatures and dates on certain paintings placed there on a whim, or did the signatures and dates convey a greater meaning or a sign of quality other than the painterly indications which can be seen today.

The painting technique of Bruegel the Elder is also contained in the first volume. The authors reveal for the first time that Bruegel the Elder was not consistent or uniform in his application of the painting’s underdrawing. The authors conclude that while some underdrawings are “sketchy and searching,” other align more closely to neatly created outlines of the completed painting.

The second volume focused on the painting technique of Brueghel the Younger, and compares a number of paintings by the Elder and Younger. For example, over 125 copies of Winter Landscape with Bird Trap exists, with attribution of some by Brueghel the Younger secured, and others not. Intriguingly, some of the Brueghel the Younger autograph copies have a small hole directly in the center of the painting. Tantalizingly, the authors hypothesized that this relates to the copying practice of Brueghel and his workshop.

The third volume focused on shedding light on Brueghel the Younger’s workshop practice. The author surmise that copying was done by tracing a cartoon. For the firs time, and in-depth discussion occurs around the number and nature of the cartoons used by Brueghel. Because Brueghel painted in a workshop setting, some works reflect greater and lesser degrees of he master’s hand. Determining which works had more or less of the workshop’s influence compared to the master’s direct participation is a central aspect of this volume of the work.

The most revelatory aspect of this volume, and perhaps of the entire work, is the proof, after much previous speculation that neither of the surviving copies of the Fall of Icarus are by the hand of Bruegel the Elder. The authors prove that the copies are by unknown followers, most likely copied after a lost Bruegelian model.

Over the coming weeks I will focus on some of the key aspects of this monograph. I hope that I will be able to convey some of the thrilling discoveries that authors bring to life in this fascinating study.

————————–

Book ordering information:

Brepols Publishers, ISBN: 978-2-930054-14-8

Price; 160 Euros / 232 dollars

Europe: info@brepols.net – www.brepols.net, North America: orders@isdistribution.com – www.isdistribution.com

“On the Trail of Bosch and Bruegel: Four Painting United Under Cross-Examination” edited by Erma Hermens

A review of: “On the Trail of Bosch and Bruegel: Four Painting United Under Cross-Examination” edited by Erma Hermens, published this year by Archetype Publications Ltd.

This publication brings together a pan-European investigation of four different, yet very similar, paintings in an exhibition titled “Tracing Bosch and Bruegel: Four Paintings Magnified.” The paintings, from the Kadriorg Art Museum, Tallinn, Estonia; The National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen; The University of Glasgow and a Private collection, look similar yet are very different. (You can compare the paintings yourself using the excellent exhibit website: http://www.bosch-bruegel.com/paintings_light.php?painting=compare) This fascinating monograph investigates the paintings from a variety of perspectives including working to answer such questions as which of the four paintings was the original.

Starting with the province of the paintings, chapter 1 reviews the relatively short history of the four works. All are not traceable before than the 20th century. Three of the paintings are similar in size and format, with the Glasgow panel the exception with its portrait format. Virtually unknown before the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Tallinn work is the least studied of the works.

Chapter 2 traces the roots of the composition, pointing out that without Max Friedlander’s attribution of the Copenhagen work in 1931 to Bruegel, this series would not be historically attached to him. Where the Copenhagen work (and to some extent the Tallinn version) are very Bruegelesque, the copy in Private hands and the Glasgow version are much more Bosch-like. The author persuasively argues that there is little Bruegel influence on the composition, with it being much indebted to Bosch motifs.

This chapter is a wonderful encapsulation of the mystery of these four paintings. While the Private painting is likely the oldest, dating from the 1530’s, of the three large canvases, it is thought to be the least like the original model. The Copenhagen version, painted some 30 – 40 years later, is probably closer to the original composition. However, the Copenhagen version is not faithful to what was likely the original’s background, with the painting in Tallinn adhering more closely to the background of the original.

Chapter 3 reviews the paintings’ materials and techniques of the studios where the paintings were executed. This chapter is especially engrossing for those coming to the subject for the first time, and features clear writing and fascinating illustrations, including presenting the method for separating a tree in order to make the planks for the paintings. The Private painting has a mark from the lumberjacks who cut down the tree, a rare example of these being visible on the reverse of a completed paintings.

A discussion of the underdrawings and the ground used to prepare the panels for paint is also discussed in this chapter. Regarding the layers of paint, the authors conclude that three of the paintings had similar build up of layers of paint, with the Private painting being the exception due to its simple preparation. Fingerprints were also found in this version and not found on the others.

Dating of the trees used to create the panels of the four paintings is a technique undertaken to assist with determining when the paintings may have been created. This process, called dendrocronology, was used in three of the four works. (Because the Glasgow’s restoration in 1987 introduced balsawood into the frame, it was not possible to attempt to date this work.) The authors note that the Copenhagen version’s planks were drawn from the same tree, which does not occur in the other two paintings. The authors conclude that the Private painting was made 30 years before the Copenhagen and Tallinn versions, within the lifetime of Bruegel but after the death of Bosch.

Chapter 5 examines the underdrawing of the paintings to determine the “handwriting” of the art works. The authors use infrared (IR) imaging techniques, including infrared reflectology to examine the underdrawings. Material used for underdrawings typically consisted of black oil chalk, which provided an outline for the painter(s) to then follow as they applied the layers of paint. It was common in workshops of the 16th century to use a so called “cartoon” or drawing covered in chalk on the reverse side of the image, placed on top of a painting and then traced. However, only the Private and Glasgow version have the characteristic “trembling” of the hand that would indicate the use of a cartoon. The authors conclude that each of the four paintings’ underdrawings as well as final paint layers were all created by different hands, and none of the four are the master model. The authors even question whether a single master model was used, believing it possible that several different version of the painting were circulating among the painters studios over the 30+ years that the works were created. The authors conclude that none of the works were created in the same studio or with the same cartoon. However, they believe that a model was on hand to create the works, given the nearly identical full foreground composition.

The 6th chapter discusses copying for the art market of the 16th century, and reviews the Antwerp art market of the time, which was said to employ twice as many artists as bread makers. Antwerp became a hub for production of copies, which accounted for fully half of the painted art output of the city during this time. There is not consensus among the authors regarding whether the works are a copy after a lost original, or a “phantom copy” (an invention made to look like the work of a popular artist). Because the coloring differs so widely across the four versions, the authors surmise that a drawing or cartoon was used. The author of this chapter concludes that the prototype was closest to the Private version, while as we saw earlier in chapter 2, the author surmised that various aspects of the Copenhagen panel was closest to the original.

In chapter 7 the author argues the case for the paintings following a lost Bosch original, rather than a Bosch 16th century revivalist. The author bases this hypothesis on the iconography of the composition, which is compatible with Bosch’s “system of norms and values.” Bosch used biblical imagery from the past to comment on the Low Countries in the early 16th Century. Like in biblical times, the typically late medieval Dutch town shown in the painting is comprised of the poor, peasants and beggars. Bosch’s lost original compels viewers to “take to heart the word of Christ” to be saved.

This monograph takes the reader on a fascinating detective hunt for the original and earliest version of the painting. For those interested in an investigation of this type within an art-historical context, this will be the perfect summertime read!

Summer Auction Highlights

The summer auction season is upon us, with Christie’s and Sotheby’s offering stellar works by Brueghel the Younger.

- Massacre of the Innocents

One of most interesting works at auction is the version of “Massacre of the Innocents” at Christie’s. It is interesting for the mystery related to the signature. From the Lot Details:

“The form of the signature on the major versions is considered to be of significance in placing them within the chronologies of Pieter the Elder’s and Pieter the Younger’s oeuvres. The Royal Collection picture is signed ‘BRVEGEL’, which is now accepted as the Elder’s signature; the Vienna version is signed ‘BRVEG’ at the extreme right edge, although the letters ‘EL’ or ‘HEL’ may have been inadvertently trimmed off; a version in Bucharest is signed ‘P. BRVEGEL’. At the time of its sale in Paris in 1979, the present version appears to have born a fragmentary date in addition to the signature, ‘.BRVEGEL. 15..’ (see Campbell, op. cit., p. 15). We are grateful to Christina Currie of KIK/IRPA for noting that the present version is unusual in that it is signed with the signature form of Bruegel the Elder after 1559, ‘.BRVEGEL.’ without an ‘H’ and without the initial ‘P’. No other versions of the Massacre of the Innocents are securely known to be signed in this way; the implications of this for its primacy in the sequence of versions painted by Brueghel the younger remains to be established.”

What happened to the date on the painting? Having the date on the work in 1979 but not present now is mysterious. Was the painting subject to a botched cleaning? Or, did a cleaning reveal that the date was likely false, and was it removed? Hopefully this mystery will be solved soon. Further, it will be very interesting to learn where this version sits in the multiple versions painted by Brueghel.

“Nord on Art” has a great write up of the upcoming Brueghel works at auction:

Brueghel – the Warhol of the Old Master market – UPDATED with sale results

Newly discovered landscape drawing by Pieter Bruegel the Elder on display

The Museum Mayer van den Bergh made a major announcement related to a new Bruegel drawing. From their news release:

From June 16 through October 14 2012, the Museum Mayer van den Bergh will host the “Pieter Bruegel Unseen! The Hidden Antwerp Collection” exhibition. For the first time ever, the museum will be displaying some 30 prints by Pieter Bruegel the Elder to the general public.

Curator Manfred Sellink, however, has another surprise in store for visitors…

In late 2011, Sellink, curator of the exhibition, Director of Musea Brugge and for years a researcher of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s body of work, received a photo of a drawing from a private collection. Sellink and Martin Royalton-Kisch, former curator of the British Museum Department of Prints and Drawings, came to the conclusion, after a thorough study, that the landscape drawing belonging to the private collector could indeed be ascribed to Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Comparisons of the paper type with drawings from the same period and an ultraviolet light test lent weight to their conclusion. For example, it appeared that the newly discovered landscape drawing’s paper was of the same Italian origin as the paper that Bruegel used during his journey to and stay in Italy from 1552 to 1554. In addition, ultraviolet light made traces of a signature visible in the bottom left corner.

The drawing of a mountain landscape with two travellers is the first unknown drawing by Bruegel that has appeared since the 1970s. The landscape drawing has all of the characteristics (composition, image structure and drawing technique) of Bruegel’s self-drawn pieces from the 1552-1555 period (see for comparison the drawings from the British Museum from the same period on the right).

Striking details such as the characteristic way in which the birds are drawn, the manner in which the leaves of the trees are continuously typified by a recurring horizontal “3”, the long parallel shading used to create depth, the manner – as swift as it is accurate – in which the two travellers are shown in the centre, the remarkable way in which the crown of the trees in the background is created using a row of thin strips, the characteristic differences between the foreground’s fluent and sturdy ink-filled pen strokes and the much thinner, more precisely laid-out background… everything points to the drawing being the work of Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

This recently discovered landscape drawing will be on display for the first time ever in the “Pieter Bruegel Unseen! The Hidden Antwerp Collection” at the Museum Mayer van den Bergh starting on June 16, 2012.

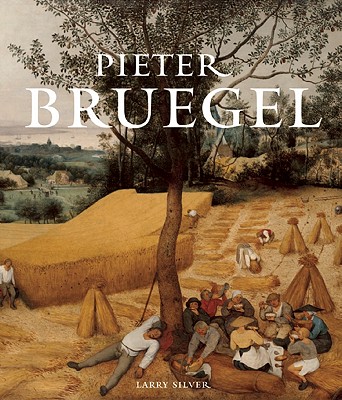

Larry Silver’s “Pieter Bruegel”: New Insights On The Old Master

A review of “Pieter Bruegel” by Larry Silver, Abbeville Press, 2011

The images created by Bruegel come thrillingly to life in this Abbeville Press monograph. This handsome volume, written by Larry Silver, Farquhar Professor of Art History at the University of Pennsylvania, puts forward new insights into Bruegel and the time in which he lived. Silver set out to document Bruegel’s output in prints, drawings and paintings by focusing on patterns and areas of interest common to these diverse media. Silver places Bruegel in the social and historical context of his time, as a commentator of the religious and political unrest occurring in the Netherlands during his short lifetime. Silver also includes information not typically found in other Bruegel monographs, documenting the rise of Bruegel scholarship at the end of the nineteenth century, when the new country of Belgium began to look for a native artist to celebrate.

Silver’s first chapter focuses on “Chris Carrying the Cross,” recently made into the fascinating film by Lech Majewski and discussed in a previous blog entry. This chapter is an excellent companion piece to the film, setting Bruegel’s work in the context of Rogier van der Weyden, who lived before Bruegel, as well as Bruegel’s contemporaries such as Joachim Beuckelaer. For Silver, “Christ Carrying the Cross” showcases Bruegel’s range of expression found in his earlier prints, as well as pointing the way to his groundbreaking final paintings, which break with the traditional staging of peasant and religious scenes.

Other chapters cover Bruegel’s life in Antwerp, his prominent patron Nicolaes Jonghelinck and his time with print maker (and future father-in-law) Hieronymus Cock. In a chapter on Bruegel as the “second Bosch,” Silver describes a fascinating transition between the “Bosch” brand, which Bruegel used early in his career, to the “Bruegel” brand, which was not only used by Bruegel but continued by his son and followers for generations.

Silver’s chapters on religion and tradition include an analysis of Bruegel’s ongoing interest in soldiers and weapons, placing Bruegel’s art in the broader context of earlier German images of important battles, such as the Battle of Pavia, which clearly had a significant influence on the artist.

It is inevitable that a Bruegel monograph would include a section on peasant labor and leisure, but Silver manages to put an interesting new spin on this oft covered subject. Building on Alison Stewart’s recent work, Silver shows Bruegel continuing and expanding the tradition of scenes found in German woodcuts. The fascinating scholarly debate between whether Bruegel’s treatment of peasants was sympathetic or moralistically critical is covered well by Silver.

One of the aspects of the monograph that I enjoyed the most was Silver’s careful treatment of lost works by Bruegel that have come down to us through copies by his sons. Silver rightly points out that these lost works deserve robust, careful consideration in the context of original Bruegel’s that survive and should not be discounted as is typical in other Bruegel monographs. Paintings such as “Wedding Procession” and “Visit to a Farmhouse” are two examples where only copies survive, but nevertheless are important components of the Bruegel oeuvre.

The final chapter, which details Bruegel’s legacy, includes an analysis of works by his sons, as well as those who copied or even forged Bruegel’s works. Silver sees this as Bruegel coming to assume a similar status as Bosch, where “Bruegelian” images and themes were adapted and repeated to great commercial success. Silver concludes the monograph by highlighting how no single scholarly consensus has emerged for Bruegel. Rather, he is viewed through the prism of the agendas of scholars who study him.

This monograph is highly recommended.